Marine composites: A new dawn?

Boatbuilders fared worse than automakers during the recent recessionary storm. As the dark clouds dispel, there is some light on the horizon.

The recession of the past two years has been unkind to many end markets served by the composites industry, but none has been harder hit than marine. With high unemployment, the mortgage crisis, and credit in short supply, the disposable household income that fueled solid marine industry growth over the past decade dried up, and so did demand for many of the new boats that frequent lakes and oceans around the world. An industry that in the mid-2000s enjoyed robust sales and growth suddenly, at the end of 2008, saw every sales metric begin a complete and unprecedented nosedive.

The year 2009 represented, by many accounts, rock bottom in the marine recession, and because of that there was nowhere to go but up as 2010 rolled around. Indeed, signs point toward a sustained, but slow, recovery. As the marine industry begins what is hoped to be the beginning of the recession’s end, CT checks in with boatbuilders and those who supply their materials to find out how the future might shape up.

Numbers that go crunch

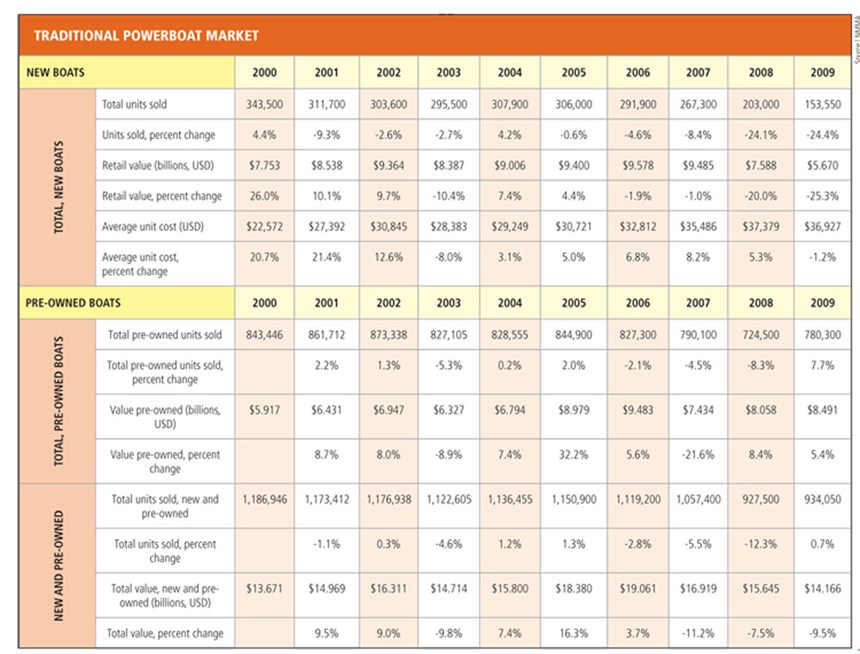

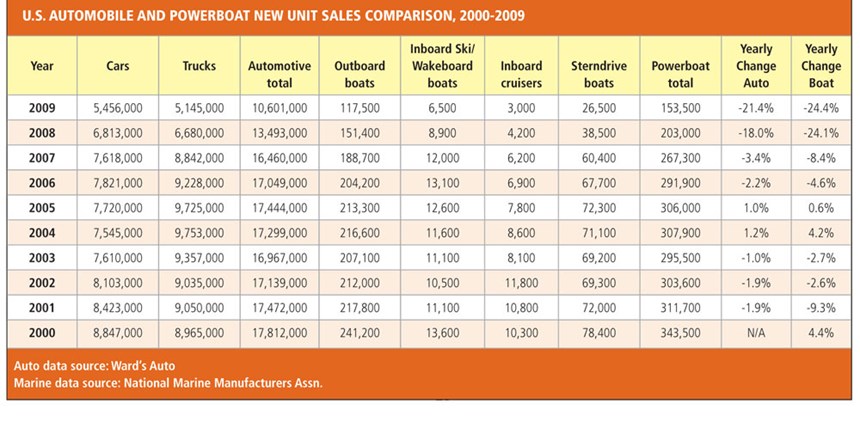

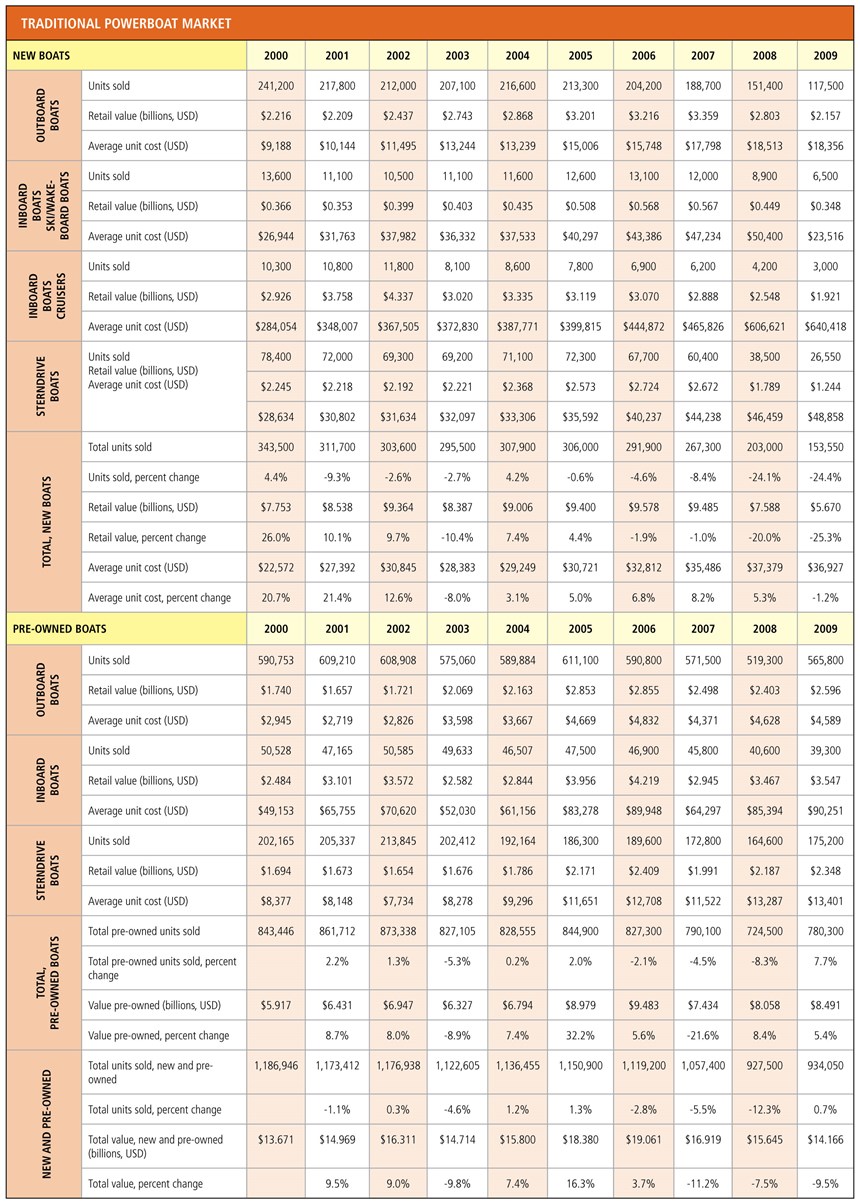

Data from the National Marine Manufacturers Assn. (NMMA, Chicago, Ill.) paint a bleak picture that most boatbuilders know well, and looking at the numbers from the last decade-plus, it’s difficult to overstate the severity of the contraction that this market suffered. The extent of the downturn varied, depending on where on the food chain a company did its marine business. Sales of new powerboats by U.S. boat manufacturers, who account for 55 percent of the worldwide market and for which a decade of reliable records were available at press time, tell the tale. For powerboat dealers, retail sales over the last decade peaked in 2001 at 311,700 units, and after that, continued to hover around 300,000 units. (See the first chart, at right. A broader set of statistics with greater detail for new and used boat sales can be viewed in the third chart.) In 2007, signs of a slowdown appeared as sales of new powerboats dropped modestly to 267,300 units, followed in 2008 by a more dramatic drop to 203,000 units. In 2009, however, the floor fell out of the marine market almost completely as sales of new boats plunged to 153,550 units. In the meantime, the total retail value of new boats dropped from a decade high of $9.578 billion (USD) in 2006 to just $5.670 billion in 2009. In the span of just three years, the value of the U.S. new boat market was cut by 41 percent, and the shipment of new boats was reduced by almost half. The U.S. auto industry, by comparison, plummeted 35 percent during the same period (see the second chart, at right).

Looking back, NMMA president Thom Dammrich puts the problem succinctly: “A normal level of inventory became a two-year supply of inventory almost overnight.”

For boatbuilders — and for the same reason — it was worse. As sales of new boats dropped, boat production dropped even faster. Dammrich says wholesale boat sales in 2009 were down 80 percent compared to 2008.

Where boatbuilders went, their composite materials suppliers followed. Many of the resin vendors contacted for this story reported declines of 75 to 80 percent in their 2009 marine business compared to 2008. “The marine market pretty much just disappeared,” says Leon Garoufalis, president and COO of distributor Composites One (Arlington Heights, Ill.), which saw its marine business drop 80 percent in 2009. “We’ve all been through downturns before, but the overall severity was unforeseen. The overall depth was just amazing.”

Fletcher Lindberg, business manager for reinforced products at resin supplier AOC (Collierville, Tenn.) says his company’s sales in the marine market dropped 75 percent at its low point last year. “The market just ceased to exist,” he recalls, noting, “It’s hard to sell resin when the [boat] plants aren’t open.”

Mike Wallenhorst, director of product management at Ashland Performance Materials (Dublin, Ohio), offers this analysis: “In 2009, while boat sales were off, boat production took a much bigger hit, creating a far bigger impact on the suppliers than the boat sales figures would lead you to expect.” Hardest hit, he says, was the 30- to 40-ft cruiser segment, a class of pleasure boats most often purchased by the upper-middle class, especially the older demographic. As the values of both homes and retirement portfolios have plummeted, says Wallenhorst, “so has the confidence of these buying groups, and therefore the sales of these boats. The only segment that seems to have taken less of a hit is the ski boat segment.” Lindberg concurs, noting an overall trend away from large boats toward smaller craft (less than 24 ft). Consumers who still want to be on the water are opting to spend less and, therefore, choose a smaller boat that fits their budget, he says.

Also evident in the data is an unusual breakdown of a previously reliable link between sales of pre-owned and new boats (see charts 2 and 3, at right). Historically, pre-owned craft have most often entered the market because the seller is upgrading to a newer model. During the downturn, however, as disposable income for boats evaporated, folks who already owned boats often sold them to raise cash and did not purchase a new boat to replace it. The result: a contracting new-boat market and a pre-owned market that held relatively steady. The pre-owned market peaked in 2002 at 873,338 units sold, and as late as 2006, was still at 827,300 units. The 2007 to 2009 time span saw a modest decline, but only to 780,300 by the end of the decade.

This, says Dammrich, forced boatbuilders to compete not only with other boatbuilders but the pre-owned market as well (see sailboat builder Chris Stanton’s comments on this phenomenon in this article's companion “Q&A” sidebar at the bottom of this page, or click on the sidebar's title under "Editor's Picks," at right). “Manufacturers were looking to develop value-priced lines that compete with pre-owned boats,” he says.

Survival: downsize or diversify

By all accounts, the boatbuilding community responded admirably, cutting costs and reducing staff as necessary. Dammrich notes that several custom boatbuilders (less than 20 units per year) were forced out of business, but he emphasizes that what he calls “right-sizing” made it possible for no large-production boatbuilder to shut its doors because of the downturn. That said, there has been no shortage of facilities closures, brand consolidations and discontinued boat lines. The most visibly stressed production boatbuilder in 2009 was Genmar Holdings (Minneapolis, Minn.; 13 brands, eight facilities, $1 billion in sales in 2007), which declared bankruptcy in early 2009 but was bought out of that hole in June 2009, with some assets purchased by equity group Platinum Equity (Beverly Hills, Calif.), some purchased by another investor group led by Irwin Jacobs (Genmar’s former chairman and CEO) and the remainder purchased by MCBC Hydra Boats (Vonore, Tenn.).

In other activity, Brunswick Boat Group (Lake Forest, Ill.), a manufacturer of more than 30 boat brands, sold its Triton Boats this year to Fish Holdings LLC (Flippin, Ark.), an affiliate of Platinum Equity. Also at Brunswick, Hatteras Yachts consolidated production of its Hatteras Yachts and CABO Yachts at its facility in New Bern, N.C. Finally, at the end of August this year, yachtbuilder Nordic Tugs (Burlington, Wash.) announced it is temporarily closing its plant, with most of the 40 employees furloughed.

One key to survival was diversification. A manufacturer of 110- to 265-ft luxury yachts that employed 500 people in 2008 but only 75 at the end of 2009, Christensen Shipyards (Vancouver, Wash.) got through by refocusing its company’s capabilities on the renewable energy sector. Company president Joe Foggia launched Renewable Energy Composite Solutions LLC (RECS), a wind turbine and hydrokinetic composite component fabrication and manufacturing specialist (see our update on composites in emerging hydrokinetic technologies by clicking on "Marine composites: A new dawn?" under "Editor's Pick's," at right).

Foggia also used the lull to adopt lean manufacturing practices, for which the company received a stimulus grant administered by Impact Washington, a nonprofit consultancy. “We could build all products — yachts, wind turbines, hydrokinetic devices — much more efficiently,” he says, “and through synergies command better pricing on materials.”

Brock Elliott, the general manager and a second-generation leader at family-owned Campion Marine Inc. (Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada), says when the recession hit “you couldn’t get small enough quick enough.” Campion has built 16- to 30-ft sport and fishing boats for 37 years and sells around the world, but when it was forced to cut its crew of 195 to 66, the decision was made to quickly diversify its business even more into other boat types, Elliott says. For example, Campion made the molds and fiberglass parts (hull, deck, retractable wings and other parts) for the $1 million, 40-ft/12.2m V40, made by Vector Powerboats (Kelowna, British Columbia, Canada). Subsequently, Vector Powerboats was commissioned to make a P1 full race version of the V40 for the Lucas Oil Scandinavian Offshore Challenge team, and Campion built the fiberglass hull, deck and other small parts.

Campion also formed a joint venture with Kelowna-based Svfara Marine Inc. to build Svfara’s SV2 and SV3 wake/surf towboats. Campion also converted part of its 100,000 ft²/9,290m² facility to refurbish old boats and now rebuilds stringers, replaces upholstery and performs other renovation services.

More importantly, says Elliott, the recession was an occasion to emphasize green technology in building its boats. In January, Campion announced that it was switching all of its boats to Ashland’s Envirez bio-resin, and it has moved away from acetone use. The company also is testing a recycled PET (polyethylene terephthalate) core material from Baltek Inc. (Northvale, N.J.).

Revival: Stability, then sustainability

Although the NMMA is projecting that 2010 will post a 15 percent decline in new boat sales compared to 2009, that is likely reflective of the end of the 2009 downturn and not a harbinger of things to come. Boat production is already on the rise, and the consensus is that the worst of the marine contraction is behind the industry. Optimism, however, is currently tempered with a large dose of reality. Marine veterans are keeping a keen eye on the demand picture.

Composites One’s Garoufalis says his company is seeing “varied levels” of activity and that “it’s great to see many of our customers getting back on their feet.” Composites One, he says, will see its marine business rise about 20 to 30 percent compared to 2009, noting that “It’s not hard to do better than virtually nothing.” He says niche builders in particular — those serving some law enforcement markets and the ski and fishing segments — are seeing more activity now, and the market in general may be weaker in the second half of the year than the first half of the year. For 2011 and 2012, he says to expect modest growth but that “ultimately, the consumer needs disposable income for the marine business to grow.”

Dammrich similarly sees slow growth over the next two years and expects it will take at least five years before the market sees annual new boat sales return to the 250,000- to 300,000-unit range.

AOC’s Lindberg calls the market “very tenuous and sensitive to macroeconomic news. Until economic security returns, consumers will hold back.” He also notes that many boatbuilders are running small inventories and produce boats only as needed. Because of this capacity contraction, rapid expansion will be difficult. “Capacity has been wiped out,” he says. “Even if we got back to 2007 levels, I don’t know where those boats would be made. It will take time to rebuild capacity.”

From the boatbuilder’s perspective, the view and mood varies. Christensen’s Foggia feels good about his new mixed-business model. “We have completed five yacht contracts and we have various other contracts in renewables along with many RFQs [requests for quotations] from very large companies in renewable energy,” he maintains, adding that “2011 looks even better.” Campion’s Elliott, however, sees several issues that could retard recovery. The euro is weakening against the U.S. dollar, depressing marine demand from Europe, and there is still some boat inventory to be worked through. “Americans don’t appear ready to buy yet,” he observes. Further, as larger boatbuilders continue to consolidate brands and reorganize, they’ll tend to dump boats into the market to generate cash, and this creates market instability.

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that Ashland’s Wallenhorst is looking first for a return to stability, and then growth: “Although marine resin volumes have improved over 2009 levels, production is still off from the high point,” he says. “There just is not enough good news out in the overall economy to give people the confidence to take on another payment. When they are willing, there is still a shortage of reasonable financing options. Our hope for the next 18 months is that boat production and sales levels will stabilize near current levels. This will allow the builders and suppliers to plan, forecast and build with confidence. Beyond 18 months we expect a long period of moderate growth of no more than 3 to 7 percent.”

Whatever comes, sentiment is that the marine industry has handled this downturn as well as could be expected and maybe saved itself in the process. “It could have been a lot worse,” says Lindberg. “I give our customers a ton of credit.”

Wallenhorst agrees. “Our customers have just gone through the worst downturn in over 20 years. Many of them have had to make very difficult decisions regarding valued employees, models and dealers,” he points out. “They have done what is necessary to survive and have maintained their composure, their integrity and their compassion through it all.”

Asked if the marine industry learned any important lessons over the last few years, Garoufalis sees no need to point fingers: “No one could have predicted this crisis,” he says. “But we do have to be more careful in the future about how we manage our business, about being efficient and keeping costs down.”

Related Content

European boatbuilders lead quest to build recyclable composite boats

Marine industry constituents are looking to take composite use one step further with the production of tough and recyclable recreational boats. Some are using new infusible thermoplastic resins.

Read MoreBiDebA project supports bio-based adhesives development for composites

Five European project partners are to engineer novel bio-based adhesives, derived from renewable resources, to facilitate composites debonding, circularity in transportation markets.

Read MoreJEC World 2024 highlights: Glass fiber recycling, biocomposites and more

CW technical editor Hannah Mason discusses trends seen at this year’s JEC World trade show, including sustainability-focused technologies and commitments, the Paris Olympics amongst other topics.

Read MoreDITF develops water-spun lignin fibers as PAN precursor alternative

Lignin fibers produced via an aqueous solution and dry spinning process result in homogeneous, smooth-surfaced fibers that are more environmentally friendly and cost-saving.

Read MoreRead Next

Developing bonded composite repair for ships, offshore units

Bureau Veritas and industry partners issue guidelines and pave the way for certification via StrengthBond Offshore project.

Read MoreVIDEO: High-volume processing for fiberglass components

Cannon Ergos, a company specializing in high-ton presses and equipment for composites fabrication and plastics processing, displayed automotive and industrial components at CAMX 2024.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)