What is the genesis of automated tape laying technology?

CW Editor-in-Chief Jeff Sloan seeks and finds the roots of automated tape-laying technology in the work done by close associates of legendary composites-industry pioneer Brandt Goldsworthy.

Earlier this year, we connected with composites veteran Rob Sjostedt, CEO of VectorSum Inc. (Irvine, CA, US) and a former associate of legendary composites innovator Brandt Goldsworthy of Goldsworthy Engineering (Torrance, CA). Rob wrote a CW: Past, Present & Future column for us in the April issue. There, he talked about the composites fabrication technologies that were developed at Goldsworthy Engineering — some of which have panned out and some of which haven’t. Among the winners, Rob mentioned automated tape laying (ATL).

This got me to wondering about the history of fiber and tape placement. Which came first, and when? It seemed likely to me that tape laying preceded fiber placement, but what was its genesis? Where and when was the first ATL conceived?

This sent me to our senior writer emeritus, Donna Dawson, who spent more than 20 years working with Brandt Goldsworthy and had a front-row seat for many of his company’s technological developments. She dug through her voluminous notes and records and suggested I try to find a 1969 (!) SAMPE paper, authored by Goldsworthy engineering sales manager Ethridge “E.E.” Hardesty, titled, “Advanced Composite, High-Modulus Tape Placement Machines.” Off to SAMPE I went, where a very helpful Robert Garcia dug up the paper for me. It was presented at the SAMPE 15th National Conference in Los Angeles.

Hardesty’s paper is remarkable for a couple of reasons. First, it outlines not what was being done to develop ATL, but what must be done. Second, it presents a well-crafted snapshot of what was then the state of the industry’s art. Hardesty notes, for example, “With the advent of company-sponsored — often with Air Force assistance — flightworthy and flight-tested structures, it is immediately evident that filament and tape placement techniques and processes thus far developed, mostly involving hand layup methods, are now in need of being transposed into First Generation production machines.”

Hardesty goes on to describe his (and, presumably, Goldsworthy’s) vision of the first three generations of tape placement machines, which he predicted would evolve through 1974. The first-generation machine would place 3-inch wide tape with a gantry-type machine, with distances dialed-in with digital thumbwheels. The second-generation machine, owing to the need to place fiber on compound curvatures, would apply 3-inch tape slit into 24 1/8-inch tows, with X-Y, X-Z and Y-Z movement capabilities. The third-generation machine would be able to reach into “any spot on any surface and begin laying tape, progress in any direction over that surface and terminate its applied tape band at any other spot on the surface. All automatically.”

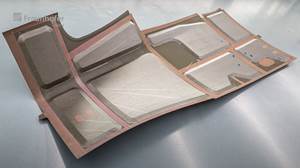

So, what happened? Well, Hardesty’s prescription was not just a well-calculated shot in the dark. Indeed, on Nov. 27, 1973, the US Patent Office issued to Harald Karlson and Ethridge Hardesty, both of Goldsworthy Engineering Inc., patent number 3,775,219 for a “Composite-Tape Placement Head.” It would, according to the patent, comprise “an integrally complete composite-tape placement head for direct attachment to a host gantry type of machine, which tape placement head is designed to precisely apply preimpregnated fiber reinforced tape to a work piece.”

The patent focuses primarily on the tape placement head, its design and features, including “tape forwarding, tape-placement, backing-film retrieval, and tape cut-off mechanical and drive functions.” It suggests the use of several fiber types — “fiberglass, lithium, boron, quartz or grown whisker crystals, etc.” — but not carbon fiber. It also suggests the use of several resin systems, including polypropylene, polycarbonate and polyester, as well as phenolics and epoxies.

Thus, it appears, automated tape placement was launched. If only Mssrs. Goldsworthy, Karlson and Hardesty could see, today, what’s become of the technology they created.

Related Content

Optimizing AFP for complex-cored CFRP fuselage

Automated process cuts emissions, waste and cost for lightweight RACER helicopter side shells.

Read MorePEEK vs. PEKK vs. PAEK and continuous compression molding

Suppliers of thermoplastics and carbon fiber chime in regarding PEEK vs. PEKK, and now PAEK, as well as in-situ consolidation — the supply chain for thermoplastic tape composites continues to evolve.

Read MoreManufacturing the MFFD thermoplastic composite fuselage

Demonstrator’s upper, lower shells and assembly prove materials and new processes for lighter, cheaper and more sustainable high-rate future aircraft.

Read MorePlant tour: Aernnova Composites, Toledo and Illescas, Spain

RTM and ATL/AFP high-rate production sites feature this composites and engineering leader’s continued push for excellence and innovation for future airframes.

Read MoreRead Next

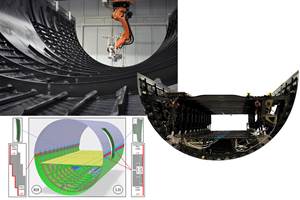

ATL and AFP: Signs of evolution in machine process control

Improved machine-control software, placement accuracy and design simulation have made automated fiber placement and tape laying machines truly production-worthy. The evolution, however, still continues.

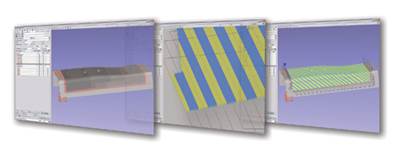

Read MoreAFP/ATL design-to-manufacture: Bridging the gap

Managing production of a structure made via fiber or tape placement often requires software-aided manipulation of the subtle differences between that which is designed and that which can be manufactured.

Read MorePlant tour: Daher Shap’in TechCenter and composites production plant, Saint-Aignan-de-Grandlieu, France

Co-located R&D and production advance OOA thermosets, thermoplastics, welding, recycling and digital technologies for faster processing and certification of lighter, more sustainable composites.

Read More