Not biting the hand that feeds you

A month since the explosion on the Deepwater Horizon offshore oil platform in the Gulf of Mexico, things don’t look good for offshore oil exploration, but the composites industry, which depends on petroleum for much of its raw materials, would be wise to consider how it might help make deepwater drilling safer.

A month since the explosion on the Deepwater Horizon offshore oil platform in the Gulf of Mexico, things don’t look good. As I write this, the still expanding slick poses the possibility of a worse ecological disaster than that caused by the infamous Exxon Valdez tanker spill in Alaska. Worse, oil now is nearing shore and threatening to wash up on the beaches and invade the marshes of Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama also has curtailed or halted the fishing and shrimping that forms the foundation for livelihoods in hundreds of communities along the Gulf Coast. Assuming the leaks can be stopped and a cleanup accomplished before the oil comes ashore, fish schools and shrimp beds still could be decimated. Oil giant BP, the platform’s owner, is footing the bill for a hugely expensive and, so far, unsuccessful attempt to halt the flow and prevent further spread through a variety of previously effective means because the well head, a mile beneath the water’s surface, can be serviced only by robots, with great difficulty.

Meanwhile, BP executives are getting grilled in Congressional hearings. Skittish investors have bailed on the British company, reducing its value by more than $30 billion. And the crisis is affecting oil industry policy making: The Republican governors of Florida and California — states with prime offshore oil potential — rescinded their support for drilling off their coastlines. President Obama has put new drilling on hold, pending an investigation, and is reportedly “reconsidering” his recent call to issue offshore permits.

This crisis will do much to put governmental focus on clean, renewable, sustainable energy production. That is a good thing and will no doubt benefit the composites industry, which is now well-positioned in the wind energy market. But this windfall should not be allowed to obscure our view of the bigger picture. Our perennial need to sell our product based on lifecycle costs, rather than upfront cost, should equip us to take the long view.

In that spirit, we must remember that, as President Obama himself recently pointed out, the pre-accident safety record of the oil and gas industry in the U.S. has been near sterling for 20 years. According to The Economist (May 8-14, 2010 issue, p. 11), there have been no serious leaks from offshore installations for more than 40 years. And we must be reminded that when the Valdez crisis hit the news, Exxon’s stock price also plunged, and its post-spill litigation plenty during the next two decades, but Exxon did not die. It went on, instead, to become the largest oil company in the world. The sinking of the Deepwater Horizon won’t sink offshore oil. It would be unwise to put all our chips into the renewables pot and not hedge our bets with continued investment in fossil fuel solutions.

Why? First, the obvious fact that, while partially bio-based composite materials are making a showing, all polymer composites require a resin component and, in many cases, fiber reinforcements that are petroleum-based. Until that is no longer true, oil exploration will be necessary. Barring quantum leaps in sustainable resin technology, composites will, for the foreseeable future, be dependent for their existence on a plentiful and reasonably priced oil supply. It would be most unwise, then, to turn our backs on the industry that feeds us. Second, although offshore oil composites reached a bit of a stall point early in this decade — the failure of a test composite riser, for example, set things back a bit — we have, nevertheless, made many inroads into platform and tubulars construction (see “Deepwater oil exploration fuels composite production,” under Editor's Picks," at right). I believe that the post-crisis oil & gas industry is likely to be powerfully receptive to any composite innovation that promises a safer oil industry future. The fact that we’ve encountered barriers in the past should not deter us from pursuing oil & gas applications, especially those that could accomplish that end. We must not be put off by setbacks. Instead, we must persevere.

Our experience in the auto industry is instructive here: Not one year ago, I sat in a trade show keynote session where an auto company exec made it very clear to the composites industry professionals in the audience that carbon fiber had no future in production cars. But in this issue, we update the news of an SGL/BMW joint venture to build a carbon fiber plant in the U.S. that will supply carbon exclusively for a new BMW commuter car (see pp. 12 & 20). In our April issue, our editor-in-chief described it as a gutsy bit of risk taking. But as noted on p. 12, by the end of April, SGL/BMW weren’t alone. Toray and Daimler have made a similar arrangement, and Zoltek is working on a serious automotive push as well. What in January looked like a brave undertaking by an adventurous pair of mavericks suddenly, and with little warning, has all the earmarks of an industry trend. Sounds like carbon and production cars are finally going to hook up after all. And sooner than anyone imagined. The lesson? Never say “never.”

To be sure, we should heartily pursue every “green” composites opportunity, not only in the wind industry, but in fuel cell power, solar power and other energy alternatives. If, in doing so, we help rid our world of the need to burn oil, so much the better for Earth and for us. Our supply of oil will last longer, and its price will moderate. But we must look beyond — and encourage our congressional representatives to look beyond — today’s disturbing news to the practical reality that oil forms the foundation for what we believe to be the future of manufacturing. And we must redouble our efforts to make offshore oil exploration a safe and sustainable enterprise.

Related Content

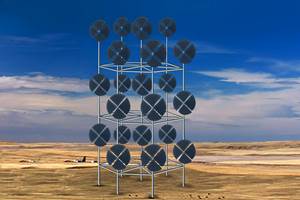

Drag-based wind turbine design for higher energy capture

Claiming significantly higher power generation capacity than traditional blades, Xenecore aims to scale up its current monocoque, fan-shaped wind blades, made via compression molded carbon fiber/epoxy with I-beam ribs and microsphere structural foam.

Read MoreHonda begins production of 2025 CR-V e:FCEV with Type 4 hydrogen tanks in U.S.

Model includes new technologies produced at Performance Manufacturing Center (PMC) in Marysville, Ohio, which is part of Honda hydrogen business strategy that includes Class 8 trucks.

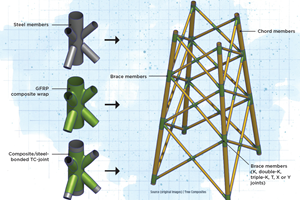

Read MoreNovel composite technology replaces welded joints in tubular structures

The Tree Composites TC-joint replaces traditional welding in jacket foundations for offshore wind turbine generator applications, advancing the world’s quest for fast, sustainable energy deployment.

Read MoreNCC reaches milestone in composite cryogenic hydrogen program

The National Composites Centre is testing composite cryogenic storage tank demonstrators with increasing complexity, to support U.K. transition to the hydrogen economy.

Read MoreRead Next

Deepwater Oil Exploration Fuels Composite Production

As the price of oil on the world market continues to climb, and as untapped land and shallow offshore oil reserves become a rarity, oil exploration companies are striking out into deepwater, developing reserves beneath the ocean floor a mile or more below the water’s surface. As a result, demand for strong yet

Read MoreAll-recycled, needle-punched nonwoven CFRP slashes carbon footprint of Formula 2 seat

Dallara and Tenowo collaborate to produce a race-ready Formula 2 seat using recycled carbon fiber, reducing CO2 emissions by 97.5% compared to virgin materials.

Read More“Structured air” TPS safeguards composite structures

Powered by an 85% air/15% pure polyimide aerogel, Blueshift’s novel material system protects structures during transient thermal events from -200°C to beyond 2400°C for rockets, battery boxes and more.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)