Alauda Aeronautics debuts crewed flying race car

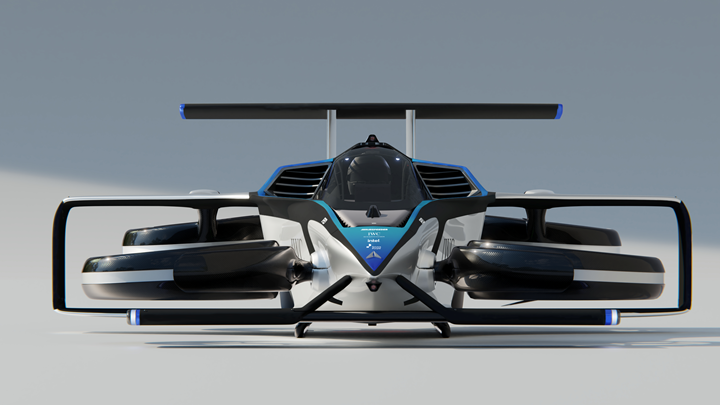

In a fusion of UAM and motorsport, the composite Airspeeder Mk4 is designed to set the bar for performance and technology for the Airspeeder Racing Championship in 2024.

The Airspeeder Mk4. See a video of the reveal. Photo Credit, all images: Alauda Aerospace

Aerospace company Alauda Aeronautics (Adelaide, South Australia) has announced development of the Airspeeder Mk4, built to be the world’s fastest hydrogen-electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) flying race car. Capable of reaching a top speed of 360 kilometers per hour (225 miles per hour) in just 30 seconds from a standing start, it is designed to set the bar for performance and technology in the new sport of piloted Airspeeder racing.

The crewed flying car, comprising a carbon fiber monocoque, is designed for maximum agility at high speeds and low altitudes. It features a sophisticated electric propulsion system, advanced aerodynamics and a takeoff weight (MTOW) of just 950 kilograms. The Airspeeder Mk4 is also said to be highly efficient, with a projected range of 300 kilometers (188 miles) while producing near-zero emissions.

“We, and the world, are ready for crewed flying car racing,” Matt Pearson, CEO, Alauda Aeronautics, says. “We have built the vehicles, developed the sport, secured the venues, attracted the sponsors and technical partners. Now is the time for the world’s most progressive, innovative and ambitious automotive brands, OEM manufacturers and motorsport teams to be part of a revolutionary new motorsport. In unveiling the crewed Airspeeder Mk4 we show the vehicles that will battle it out in blade-to-blade racing crewed by the most highly-skilled pilots in their fields.”

The Airspeeder Mk4 is powered by a 1,000-kilowatt (1,340-horsepower) turbogenerator that feeds power to the batteries and motors. Specifically designed for use in eVTOLs, the technology enables green hydrogen to be used as fuel, providing safe, reliable and sustainable power over long distances and flight times. In addition, Alauda Aeronautics’ demonstrator “Thunderstrike” engine incorporates a combustor made using 3D printing techniques developed in the space industry for rocket engines. The combustor’s design keeps the hydrogen flame temperature relatively low, reducing nitrous oxide (NOx) emissions.

Unique to the vehicle is its gimballed thrust system, which uses an artificial intelligence (AI) flight controller to individually adjust four rotor pairs mounted on lightweight, 3D-printed gimbals. Ultimately, this makes the Mk4 handle “less like a multicopter and more like a jet fighter or Formula 1 racing car.”

Alauda Aerospace plans to begin flight testing the Mk4 chassis and powertrain, including the first crewed flights of the airframe, in the first quarter of 2023. The aircraft will be ready to take the start line at the Airspeeder Racing Championship in 2024.

The company is already looking beyond racing to a world where private flying cars are a daily reality, and a viable means of urban transport. Its team of engineers and designers, drawn from companies including Airbus, Boeing, Ferrari, MagniX and McLaren, are confident its technologies could make air travel faster, more efficient, more environmentally friendly and more accessible than ever before.

“You will see these technologies on the racetrack. However, eVTOLs are already a trillion-dollar industry and we see a very substantial market for private flying cars emerging in the near future,” Pearson says. “In conventional aerospace, there are about as many private jets as there are commercial jets in operation. We believe it could be the same with flying cars one day, with a roughly similar number of commercial taxis and private cars initially. Once we can sell you a flying car for the same price as a Tesla, you’ll quickly see the balance shift. Today, private cars outnumber taxis by about 300 to one, so the potential for people to own and drive their own flying car one day is enormous. It’s a very exciting time.”

Related Content

The lessons behind OceanGate

Carbon fiber composites faced much criticism in the wake of the OceanGate submersible accident. CW’s publisher Jeff Sloan explains that it’s not that simple.

Read MoreBio-based acrylonitrile for carbon fiber manufacture

The quest for a sustainable source of acrylonitrile for carbon fiber manufacture has made the leap from the lab to the market.

Read MoreInfinite Composites: Type V tanks for space, hydrogen, automotive and more

After a decade of proving its linerless, weight-saving composite tanks with NASA and more than 30 aerospace companies, this CryoSphere pioneer is scaling for growth in commercial space and sustainable transportation on Earth.

Read MoreNatural fiber composites: Growing to fit sustainability needs

Led by global and industry-wide sustainability goals, commercial interest in flax and hemp fiber-reinforced composites grows into higher-performance, higher-volume applications.

Read MoreRead Next

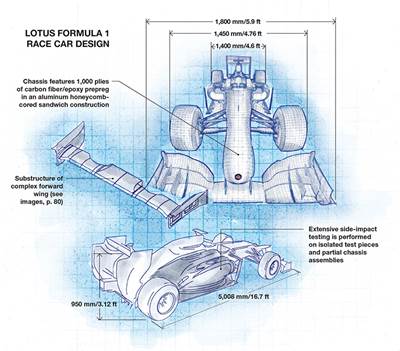

Formula 1 team optimizes car design-to-build process

FEA-to-CAD translation tool opens doors to cross-department communication and frees up time for R&D and test-piece manufacture.

Read MoreEvolution of the one-piece, all-composite Funny Car body

Large, one-piece drag racing vehicle bodies require extreme lightweighting and precise layup skills. Specialist MTCcorp shares how its John Force Racing Funny Cars have evolved over the past 25 years.

Read More“Structured air” TPS safeguards composite structures

Powered by an 85% air/15% pure polyimide aerogel, Blueshift’s novel material system protects structures during transient thermal events from -200°C to beyond 2400°C for rockets, battery boxes and more.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)