Has composites innovation reached "the stall?"

Columnist Dale Brosius reflects that composites innovation, like meat partway through the smoking process, has reached a temporary stalling point.

When I am home, I fire up the grill at least once per month, even during the winter — and multiple times per week during the summer. Sometimes it’s a quick steak or salmon on the gas grill, and other times it’s cooking on my ceramic Big Green Egg smoker using the “low and slow” approach at temperatures between 225°F and 275°F. In fact, I outlined this column while I had a whole chicken cooking away in the Egg, making the main course for a Thursday dinner. I don’t use the smoker only in the summer months, though — I also make turkey in November and pastrami in March. And once you’ve had smoked prime rib for Christmas dinner, you’ll never want to roast it in the oven again. Trust me, it’s that good.

I grew up in Texas, where barbecue is a tradition and beef brisket is king. I’ve also traveled enough to appreciate smoked pulled pork shoulder. Both meats require a whole day to properly prepare, so about six to 10 weekends each year I smoke either a brisket or a couple of pork shoulders. Both cook at 225°F, the lower end of the smoking range, so they go on early in the morning. I insert a couple of temperature probes (just like thermocouples in curing composites), with a goal to hit about 203°F as the finish temperature before pulling the meat off to rest before slicing or shredding.

Once these big hunks of meat go on the smoker, they start to heat up internally at a rate that suggests they’ll be done way before dinner. But somewhere around the four- to six-hour mark, when the internal temperature reaches 150 to 170°F, the temperature stops climbing. And sits there. For hours. For those new to this phenomenon, panic starts to set in. Will this get done to feed the hungry group I invited over for dinner tonight?

This point in the cook is called “the stall,” and there are multiple theories about what is happening, but the most scientific explanation is that the meat is going through evaporative cooling, losing moisture, and indeed, at some point in time, the internal temperature will resume its rise to the desired endpoint. Some purists insist on waiting it out (which could make total cook times more than 12 hours), but I, as well as many competition cooks, rely on what is called the “Texas crutch.” After the meat hits the stall, and has seen smoke for about six hours, it has built a good crust, or “bark,” so we wrap the shoulder or brisket tightly in aluminum foil and return it to the smoker. Shortly, the magic happens, and in about two to three hours, you reach completion. The foil traps the moisture, creating a braising fluid, and ensures a succulent, melt-in-your-mouth outcome. And happy dinner guests!

So, aside from the aforementioned use of thermocouples, what does all this barbecue talk have to do with composites? Fair question. Frankly, after years of rapid improvements in composites manufacturing technology, the composites industry seems to have hit its own version of “the stall.” Thermoset curing times are significantly lower than when BMW introduced the carbon fiber-intensive i3 and i8 in 2013, yet no other global automotive OEMs have followed suit, and none appear to be on the verge. Injection overmolding and stamping with thermoplastics have matured significantly as well, but this technology is not yet widespread. We have multiple processes with the capability of producing 100,000 to 200,000 parts per year from a single mold, but where are the high-volume applications?

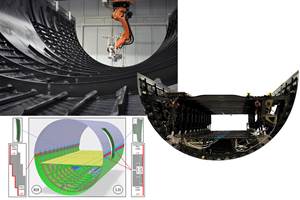

It’s not just automotive. In aerospace, we have new technology to infuse and cure large airfoils outside the autoclave, and we’ve seen plenty of innovations to speed fabrication of thermoset and thermoplastic fuselage structures. Such technologies may allow for production of 60-100 single aisle aircraft per month, but Boeing and Airbus seem nowhere close to announcing composites-intensive replacements for the 737 and A320 models.

Across the spectrum, we have improved the techno-economic competitiveness of composites and through modest volume applications, continue to see industry growth. Just not the big game-changing quantities that always seem to be “right around the corner.” Like the barbecue purists, we can simply keep fueling the fire, patiently waiting for the outcomes we know should eventually come. Or, even better, can we find a composites version (or versions) of the Texas crutch and get there much sooner?

Related Content

Plant tour: Albany Engineered Composites, Rochester, N.H., U.S.

Efficient, high-quality, well-controlled composites manufacturing at volume is the mantra for this 3D weaving specialist.

Read MoreManufacturing the MFFD thermoplastic composite fuselage

Demonstrator’s upper, lower shells and assembly prove materials and new processes for lighter, cheaper and more sustainable high-rate future aircraft.

Read MorePlant tour: Middle River Aerostructure Systems, Baltimore, Md., U.S.

The historic Martin Aircraft factory is advancing digitized automation for more sustainable production of composite aerostructures.

Read MoreASCEND program update: Designing next-gen, high-rate auto and aerospace composites

GKN Aerospace, McLaren Automotive and U.K.-based partners share goals and progress aiming at high-rate, Industry 4.0-enabled, sustainable materials and processes.

Read MoreRead Next

“Structured air” TPS safeguards composite structures

Powered by an 85% air/15% pure polyimide aerogel, Blueshift’s novel material system protects structures during transient thermal events from -200°C to beyond 2400°C for rockets, battery boxes and more.

Read MoreDeveloping bonded composite repair for ships, offshore units

Bureau Veritas and industry partners issue guidelines and pave the way for certification via StrengthBond Offshore project.

Read MorePlant tour: Daher Shap’in TechCenter and composites production plant, Saint-Aignan-de-Grandlieu, France

Co-located R&D and production advance OOA thermosets, thermoplastics, welding, recycling and digital technologies for faster processing and certification of lighter, more sustainable composites.

Read More