Modeling fabric materials for better parts

Multiaxial fabric maker Formax is involved in a multi-year endeavor to simulate the behavior of dry fabrics during the molding process.

Share

Read Next

It’s one thing to manufacture and sell a composites-related product — it’s another to truly understand how that product will behave during processing and cure. Multiaxial fabric maker Formax (Narborough, Leicester, U.K.) is involved in a multi-year endeavor to simulate, in partnership with several research and university entities, the behavior of dry fabrics during molding. Tom James, Formax’s director of innovation and leader of the modeling effort, says that the simulation research was spurred by customers interested in high-volume production and parts with complex shapes, who want to reduce their risks before any tools are cut — ultimately, the automotive industry.

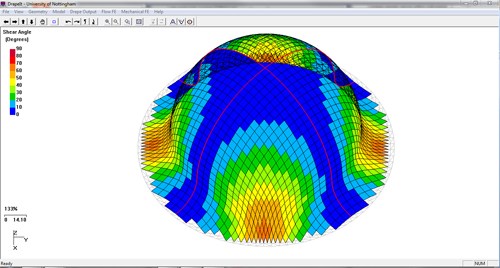

James breaks down composites simulation into three major areas: 1) simulating drape, or how dry fabric will conform to the tool, or potentially wrinkle; 2) simulating flow of resin through a fabric in a tool, a problem that many have tackled, and 3) simulating how a finished part performs in service, a fairly well-understood exercise. It’s the first item that Formax is tackling, along with colleagues at the University of Nottingham through a Knowledge Transfer Partnership, the University of Cambridge and the Warwick Manufacturing Group (Coventry, U.K.). He explains that modeling dry fabric movement is very difficult because it is the “most non-linear” problem out there, i.e., no factor is directly related to another in a one to one fashion. “The material is non-linear, the material deformations are large and the loads and boundary conditions change during forming.”

The group is investigating a variety of codes that include Abaqus from Dassault Systèmes (Waltham, Mass.), PamForm’s FE multi-physics solver from ESI Group (Rungis, Cedex, France), as well as several different finite element analysis (FEA) non-linear crash analysis codes that the group has adapted to dry materials. Formax does not yet own its own software license, and participates in the knowledge transfer group strictly on a non-commercial, research and development basis for now, James explains.

“We realized that we had to be very knowledgeable about our own fabrics. We wanted to be prepared if a customer came to us and said ‘We’d like a quadraxial fabric, and please send us all the data about it so that we perform our computer analysis,’” he says. That meant creating a data base, for all of Formax’s many fabric styles, of the key material input parameters, shown in the table below — a task James describes as “time-consuming and expensive.” Each fabric was (or is being) lab tested using industry-accepted methods to generate th e material characteristics, in each fiber direction, and then those properties were physically validated using a double hemisphere (lozenge) tool in the Formax lab. The model results for a particular fabric are tweaked slightly if required to more closely match the tested reality. Eventually this testing/validation step may be eliminated, says James, but “we’re not there yet.”

To better illustrate what James and the partner group are undertaking, he cites a hypothetical structural automotive part, such as a B-pillar. The auto OEM’s engineers would design the part, and a tool, and would then come to Formax for a carbon fiber multiaxial, for example, a 0/±45/90, with a desired areal weight. Then, Formax would enter that fabric’s properties into PamForm (or another code) and create a “base” fabric simulation, which would show their customer how that fabric would behave in the mold — how would the fibers orient within the mold shape, the friction generated, locking angle, wrinkle or bridge formation, would the fabric “ladder” along the edge, and what stresses would be created. It would also illustrate the fabric’s permeability within the mold, to help define mold fill and process cycle time.

From that base condition, the computer simulations give Formax the ability to improve or optimize the fabric for that customer’s hypothetical B-pillar, says James: “We can run hundreds of simulations, changing just one thing each time, to improve fabric shear modulus, or bending stiffness, for example.” Take stitch length: in a carbon fiber multiaxial, the properties of the carbon fiber itself dominate. But, he says, the stitches are modeled as another fabric element, less stiff than the carbon. The stitches create friction between the carbon tows, causing local compression forces that affect drapability. Formax could change stitch length or style, from pillar to tricot, for example, to optimized the fabric to the mold and application. “This modeling has forced us to think about different stitch styles, and to do things we might not have tried otherwise,” adds James.

“Lots of companies offer a fabric with ‘high drape,’ but often they can’t give quantitative information to truly define fabric behavior,” concludes James. “As more high-volume automotive parts develop, we will have the capability to optimize and customize fabrics through simulation.”

Click here to view a PDF of Formax's fabric data input parameters to model simulation codes.

Related Content

Composites-reinforced concrete for sustainable data center construction

Metromont’s C-GRID-reinforced insulated precast concrete’s high strength, durability, light weight and ease of installation improve data center performance, construction time and sustainability.

Read MoreCCG FRP panels rehabilitate historic Northamption Street Bridge

High-strength, composite molded, prefabricated panels solve weight problems for the heavily-trafficked bridge, providing cantilever sidewalks for wider shared use paths.

Read MoreGatorbar, NEG, ExxonMobil join forces for composite rebar

ExxonMobil’s Materia Proxima polyolefin thermoset resin systems and glass fiber from NEG-US is used to produce GatorBar, an industry-leading, glass fiber-reinforced composite rebar (GFRP).

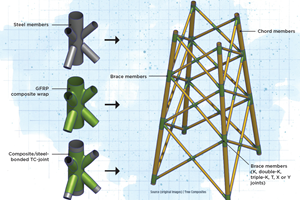

Read MoreNovel composite technology replaces welded joints in tubular structures

The Tree Composites TC-joint replaces traditional welding in jacket foundations for offshore wind turbine generator applications, advancing the world’s quest for fast, sustainable energy deployment.

Read MoreRead Next

Developing bonded composite repair for ships, offshore units

Bureau Veritas and industry partners issue guidelines and pave the way for certification via StrengthBond Offshore project.

Read MorePlant tour: Daher Shap’in TechCenter and composites production plant, Saint-Aignan-de-Grandlieu, France

Co-located R&D and production advance OOA thermosets, thermoplastics, welding, recycling and digital technologies for faster processing and certification of lighter, more sustainable composites.

Read MoreAll-recycled, needle-punched nonwoven CFRP slashes carbon footprint of Formula 2 seat

Dallara and Tenowo collaborate to produce a race-ready Formula 2 seat using recycled carbon fiber, reducing CO2 emissions by 97.5% compared to virgin materials.

Read More