Boeing offers insight on 787 composites lessons

John Byrne, VP aircraft materials and structures at Boeing, has a bone to pick with the composites industry in general and the carbon fiber community in particular.

John Byrne, VP aircraft materials and structures at Boeing Commercial Airplanes, speaking at CompositesWorld's Carbon Fiber 2014 conference, Dec. 10, 2014.

One of the headliners on day one of CompositesWorld's Carbon Fiber 2014 conference this week (La Jolla, CA, US) was John Byrne, VP aircraft materials and structures at Boeing Commercial Airplanes (Seattle, WA, US). Byrne is, effectively, head of purchasing for Boeing and thus was and is on the front lines of the Boeing supply chain, and was a crucial decision-maker when the company chose to use composites to fabricate primary structures on the 787.

Byrne was decidedly optimistic to start, offering a variety of datapoints designed to highlight the health of passenger air travel. These data included:

- Passenger air traffic up 6% in 2014

- Global load factors (utilization) 80%

- Utilization up 10-15% since 2003

- Global airline profitability at an all-time high of $18 billion

- Parked fleet rate of 2.5%, at or near an all-time low

In addition, he noted that the Chinese are traveling more and more outside of China, and overall passenger growth rates are more than the historical average.

The upward trends carry through to Boeing, as well. The company is currently building 63.3 planes a month (all models) and has a record backlog that is geographically and model mixed. The company is building 10 787s a month right now, and plans to increase that to 14 by 2018.

Yet, when it comes to composites and the 787, Byrne sounded more like a shopper suffering from buyer's remorse than the owner of an aircraft smartly assembled from the most advanced materials the world has to offer. As proof, he offered his take on several problems with the composites industry supply chain and the application of composites to the 787:

- The composites industry (compared to the metals industry) is relatively immature and ill-equipped to meet the material and fabrication needs of Boeing

- Composites in general are poorly understood by Boeing designers and engineers and therefore are not employed optimally

- The same basic combination of fiber reinforcement and resin matrix were applied on all parts and structures on the 787

- Composites use on the 787 should have been more varied and applied more selectively to meet discrete mechanical loading requirements

The crux of the problem with composites vis-a-vis the 787, said Byrne, is that the composites industry's immaturity makes capital outlay unusually expensive. This in and of itself might be tolerable at the right volume, but the 787 build rate has incrementally increased more than anticipated, Byrne said, which has driven material prices higher than Boeing would like. Byrne went as far as to state that if Boeing knew then what it knows now, "material decisions might have been very different on the 787."

The composites industry's biggest sin, however, seems to be that it's not similar enough to the metals industry. Byrne noted specifically that materials standardization in metals allows Boeing to avoid sole sourcing, which keeps costs low and the supply chain moving. It means, for example, that aluminum 123 from supplier ABC is manufactured with the same ingredients to the same specifications and properties as aluminum 123 from supplier XYZ. The carbon fiber supply chain, Byrne said, needs to follow the same model, which, he argued, only comes with better industrialization and more material standardization.. Bottom line, said Byrne, the composites industry needs to grow up, and quickly.

Of course, this is not the first time that composites have been asked to be more metal-like. The non-linear nature of composites is at once attractive and repulsive to potential and actual customers alike, and has been for years. The demand, however, that carbon fiber manufacturers standardize their products is a tricky one. The recipe on which carbon fiber production is based depends greatly on the material inputs, and the number one ingredient is the polyacrylonitrile (PAN) precursor, which is proprietary to each manufacturer. The PAN, you could argue, is a substantial competitive advantage of Hexcel, Toray, Toho-Tenax, SGL, and every other carbon fiber supplier. Because of this, Toray's T1000 carbon fiber is comparable to but distinctly different than Hexcel's IM9, just as your mother-in-law's apple pie is comparable to but distinctly different than your mother's apple pie.

Carbon fiber standardization of the type demanded by Byrne seems highly unlikely given the parameters under which carbon fiber manufacturing operates today. Might it be possible, however, for carbon fiber suppliers to agree to make a certain fiber that meets a given and established set of mechanical specifications, even if the "ingredients" remain proprietary? Perhaps, and maybe that would be enough to satisfy Byrne. But such cooperation is not in the offing, and may never be.

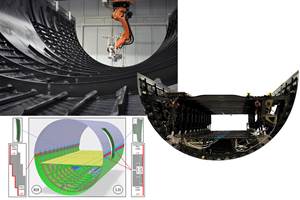

In the meantime, and despite whatever misgivings it has about carbon fiber on the 787, Boeing has decided to equip the 777X with carbon fiber wings with the same material supplier (Toray) using the same basic architecture as on the 787. Perhaps most significantly, the 777X wings will be fabricated by Boeing in Seattle, which is a departure from the supplier partnership model established with the 787.

Looking further ahead at the next big commercial aerospace programs — replacements for the A320 and 737 — there appears to be in the carbon fiber community some resignation to the fact that the fuselages in these craft will likely be aluminum, even if the wings are composite. But such programs are probably more than a decade away, which means the composites industry still has time to, as Byrne suggested, grow up and once again earn their way onto aircraft.

Related Content

Next-generation airship design enabled by modern composites

LTA Research’s proof-of-concept Pathfinder 1 modernizes a fully rigid airship design with a largely carbon fiber composite frame. R&D has already begun on higher volume, more automated manufacturing for the future.

Read MoreManufacturing the MFFD thermoplastic composite fuselage

Demonstrator’s upper, lower shells and assembly prove materials and new processes for lighter, cheaper and more sustainable high-rate future aircraft.

Read MoreCombining multifunctional thermoplastic composites, additive manufacturing for next-gen airframe structures

The DOMMINIO project combines AFP with 3D printed gyroid cores, embedded SHM sensors and smart materials for induction-driven disassembly of parts at end of life.

Read MoreThe potential for thermoplastic composite nacelles

Collins Aerospace draws on global team, decades of experience to demonstrate large, curved AFP and welded structures for the next generation of aircraft.

Read MoreRead Next

All-recycled, needle-punched nonwoven CFRP slashes carbon footprint of Formula 2 seat

Dallara and Tenowo collaborate to produce a race-ready Formula 2 seat using recycled carbon fiber, reducing CO2 emissions by 97.5% compared to virgin materials.

Read MoreVIDEO: High-volume processing for fiberglass components

Cannon Ergos, a company specializing in high-ton presses and equipment for composites fabrication and plastics processing, displayed automotive and industrial components at CAMX 2024.

Read MoreDeveloping bonded composite repair for ships, offshore units

Bureau Veritas and industry partners issue guidelines and pave the way for certification via StrengthBond Offshore project.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)