Composites: Past Present Future: Is the Window Still Open for Carbon Fiber in Automobiles?

The day I was asked to write this column, I was driving to Dayton, Ohio, and was passed by a Mitsubishi Eclipse sporting a carbon fiber hood. With the weave pattern showing through the shining clearcoat, the aggressively styled hood gave the car a more powerful look — one of speed and agility — than the OEM version

The day I was asked to write this column, I was driving to Dayton, Ohio, and was passed by a Mitsubishi Eclipse sporting a carbon fiber hood. With the weave pattern showing through the shining clearcoat, the aggressively styled hood gave the car a more powerful look — one of speed and agility — than the OEM version ever could have. Of course, this hood was purchased in the aftermarket, which has embraced carbon fiber in a big way, especially for the growing “tuner” market. While it might have been slightly lighter than the original steel hood, I doubt it offered all the benefits available when carbon fiber is designed from scratch into OEM automotive components.

Carbon fiber continues to have great appeal to designers and manufacturers, especially as fuel prices continue to rise. When carbon is used to maximum advantage, weight savings of up to 75 percent over steel components are possible. However, cost and availability hurdles relegate it to niche status, and one has to wonder if it will ever become a practical option for high-volume vehicles.

Carbon fiber has an interesting history of use in cars. Back in the mid-1970s, right after the famous “oil embargo,” Ford Motor Co. (Dearborn, Mich.), through its aerospace division, built an all-carbon composite LTD (including the body-in-white), showing tremendous weight savings, albeit at a very high cost, considering that the only fiber available at the time was an expensive aerospace grade. Carbon saw production volumes in the late 1980s and early 1990s in driveshafts (or prop-shafts, as they are called in some parts of the world). Some of these shafts were all carbon and resin, others were hybrids with glass fiber, and one high-volume version had 36K tow carbon pultruded over a thin aluminum sleeve. My first exposure to carbon fiber in an automotive part came when I was selling Dow vinyl ester resin into a filament wound driveshaft application for the Ford Econoline van in 1984. When the fiber supply became tight and prices jumped around 1992, these applications all disappeared.

For most of this period, pioneers in Formula One auto racing led the way in moving from aluminum to carbon fiber. They were followed by innovators in other racing circuits, who made the move in SCCA TransAm, GTP racing and then Indy cars. I was exposed to this market when I worked for Fiberite and helped CART, the governing body at the time for the Indy league, write the material specifications for the chassis. In fact, our material was used to build the first certified all-carbon Indy car chassis, driven by the TruSports team. Today, carbon fiber is a given in these racing vehicles.

Racing applications spurred carbon fiber use in street-legal automobiles, which peaked from 2000 to 2005, most notably in “supercars”: the Ferrari Enzo and the Lamborghini Murciélago, followed shortly after by the Porsche Carrera GT and the McLaren Mercedes SLR. Some were produced in volumes up to 500 per year. All made extensive use of carbon fiber not only in body panels but also in the structure, or “monocoque,” of the vehicle. These inspired a handful of niche vehicle producers, mostly in the U.K., to introduce carbon-intensive but lower-cost sports cars in volumes of 25 to 250 per year.

More important, the major OEMs jumped into the market, lured by a chronic oversupply of fiber and depressed pricing in the wake of aerospace cutbacks that followed 9/11, and supported by active development efforts on the part of fiber suppliers, who were exploring new markets. Although the OEMs offered carbon fiber only on portions of the vehicle, those parts were produced in higher unit volumes. Examples include the front-end structure of the Dodge Viper, the rear deck inner panel on the Ford GT, and the spoiler on the Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution. I was integrally involved in the development and production of the 2004 Chevrolet Corvette Z06 carbon fiber hood, offered in a limited edition of 2,500 vehicles. Using a specially developed, fast-curing prepreg and lean manufacturing techniques, we were able to run up to eight autoclave cycles per day, a first for the advanced composites industry. During the same period, we developed the lightweight fenders for the current Corvette Z06, with volumes now up to 7,000 vehicles per year. Even carbon driveshafts made a return, produced in volumes up to 150,000 annually for several lines of Japanese vehicles.

What the fiber suppliers didn’t know, or knew and didn’t reveal, was that the low material prices weren’t sustainable. When the aerospace market revived in 2004 and supply tightened, the auto industry was the first to feel the pinch. A number of planned projects were cancelled due to lack of fiber and high prices, and automakers became very skeptical about the material’s future. Each fall, at the Society of Plastics Engineers’ Automotive Composites Conference, we have several panel discussions in which the prospects for carbon fiber use in automobiles are hotly debated. While everyone acknowledges the benefits offered by carbon fiber, the lack of affordable materials and the absence of effective mass-production techniques for thin, lightweight carbon composite structures make the task a daunting one, indeed. Much of the momentum from the first half of the decade has been lost.

Is the window of opportunity closed for carbon fiber? None of the traditional supercar manufacturers appear to be planning carbon-intensive follow-on vehicles The Enzo and Carrera GT are out of production. The SLR is winding down, and Mercedes has stated they don’t have another on the drawing board. The newer Ferraris are mostly aluminum with a little carbon thrown in here and there. While the Murciélago is being produced as a roadster in limited volume, no new design appears to be imminent. Most of the major OEM projects are out of production: the Ford GT run ended two years ago. The Viper is still in production, but at lower rates, and while there is a street-legal racing version available with carbon body panels, only 100 are produced each year. GM, alone among the big OEMs, still shows confidence in the material, with a number of carbon components on the Corvette ZR1, slated for 2,000 vehicles per year. Set to enter production this fall, its hood, roof, roof bow, fenders, rocker molding and front splitter are carbon (the roof, roof bow, splitter and rocker moldings have exposed carbon weave), with doors, rear quarter panels and rear hatch in conventional SMC. While the aftermarket continues to produce carbon hoods, spoilers, wheels and a variety of other components to satisfy growing interest, carbon’s automotive future is anything but clear.

So, what’s being done to address the affordability issues? From the fiber side, all the fiber producers are bringing additional capacity on stream, but this is not likely to return fiber pricing to levels seen in 2002. Efforts to carbonize a new low-cost textile precursor, now underway at Oak Ridge National Labs (Oak Ridge, Tenn.) look promising, although the fiber is expected to have properties below those of traditional materials. Perhaps a fiber with 80 percent of the properties at half the price of traditional fiber will be suitable for higher volume manufacturing techniques, such as SMC or thermoplastic stamping. If so, the demand curve could head up rapidly. But more effort will be needed in higher rate processing of continuous fiber forms to take full advantage of the material. My conversations with the OEMs indicate that the window still remains open, but suppliers should expect to make long-term commitments. And me? I’m looking forward to test driving that new Corvette ZR1 this fall!

Related Content

Matrix Composite highlights carbon fiber SMC prepreg Quantum-ESC

Prepreg produced by LyondellBasell features high flow, rapid tool loading capabilities.

Read MoreGraphene-enhanced SMC boosts molded component properties

CAMX 2023: Commercially sold GrapheneBlack SMC from NanoXplore increases part strength, stiffness and provides other benefits for transportation, renewable energy, energy storage and industrial markets.

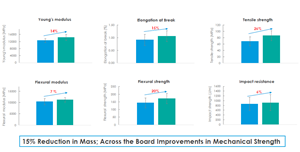

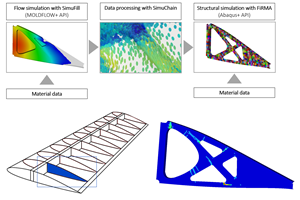

Read MoreImproving carbon fiber SMC simulation for aerospace parts

Simutence and Engenuity demonstrate a virtual process chain enabling evaluation of process-induced fiber orientations for improved structural simulation and failure load prediction of a composite wing rib.

Read MoreAOC introduces UV-Resistant Automotive System for SMC parts

AOC’s novel formulation, tested in the lab and in real-world environments, delivers a deep black, molded-in color that resists fading and offers high scratch resistance.

Read MoreRead Next

Developing bonded composite repair for ships, offshore units

Bureau Veritas and industry partners issue guidelines and pave the way for certification via StrengthBond Offshore project.

Read MoreVIDEO: High-volume processing for fiberglass components

Cannon Ergos, a company specializing in high-ton presses and equipment for composites fabrication and plastics processing, displayed automotive and industrial components at CAMX 2024.

Read MorePlant tour: Daher Shap’in TechCenter and composites production plant, Saint-Aignan-de-Grandlieu, France

Co-located R&D and production advance OOA thermosets, thermoplastics, welding, recycling and digital technologies for faster processing and certification of lighter, more sustainable composites.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)