DYNAPIXEL: automated, reconfigurable molds

CAD-driven system cuts time for design iterations, enables cost-effective customized jigs and molded parts.

SOURCE for all images | CIKONI

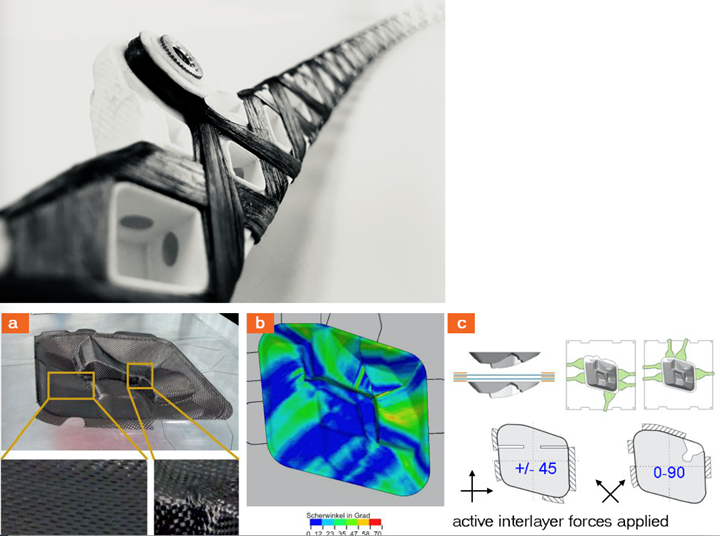

CIKONI (Stuttgart, Germany) is an engineering company that specializes in composites design, simulation, automation and process innovation. CW has reported on a number of the company’s developments, including its use of 3D-printed cores and 3D filament winding to produce lightweight truss structures (see “Filament winding, reinvented”) and its work with preforming, including draping simulations and tension devices to prevent wrinkles and other defects (see “Preforming goes industrial: Part 2”). The latter is actually how DYNAPIXEL originated.

Examples of CIKONI’s composites developments include (top) 3D filament winding carbon fiber onto 3D-printed plastic core for a lightweight automotive truss and (bottom) draping simulation for automotive preforming. SOURCE for all images | CIKONI.

“We do a lot of draping simulations,” says Farbod Nezami, one of CIKONI’s co-founders. “The OEMs have good material data, but we always need a mold to validate the simulation. We wanted a system that would allow us to iterate designs on a daily basis.” The conventional process chain for molds takes weeks: part design, mold design, quotation and purchase process, machining/production of the mold, surface preparation and delivery. “With DYNAPIXEL, we simply use the CAD data to generate the mold surface,” says Nezami. “Now, if we have a draping issue, we change the CAD geometry and have the ability to produce a small prototype in a couple of hours.”

Automated system for reconfigurable molds

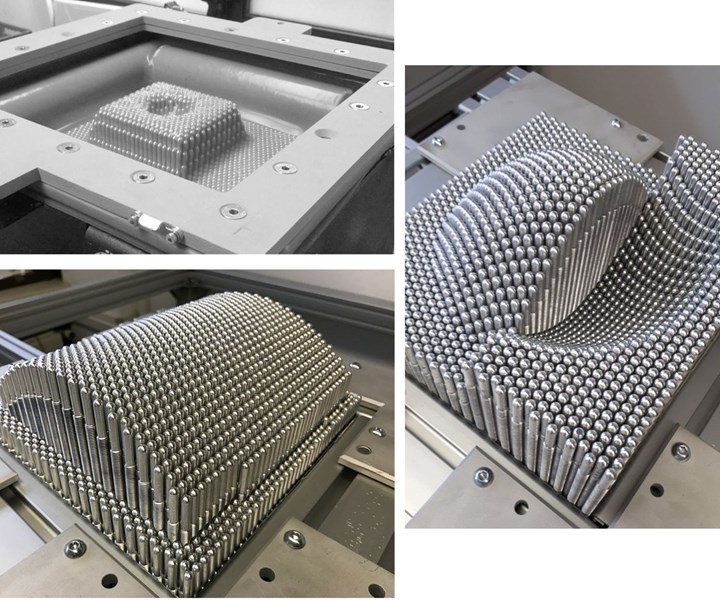

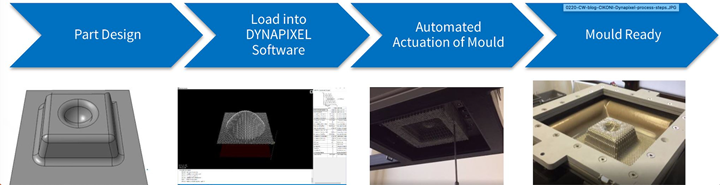

“There is no manual manipulation,” Nezami explains. “The process starts with the digital data from the part design, which is loaded into the DYNAPIXEL software. The software then generates the control array for actuating the pins and managing the parameters.”

The idea of using actuated pins to provide a reconfigurable mold has been used for decades in metalworking and recently adapted for composites by Adapa adaptive moulds (Aalborg, Denmark), discussed in CW’s 2017 feature on reconfigurable tooling. How is DYNAPIXEL different?

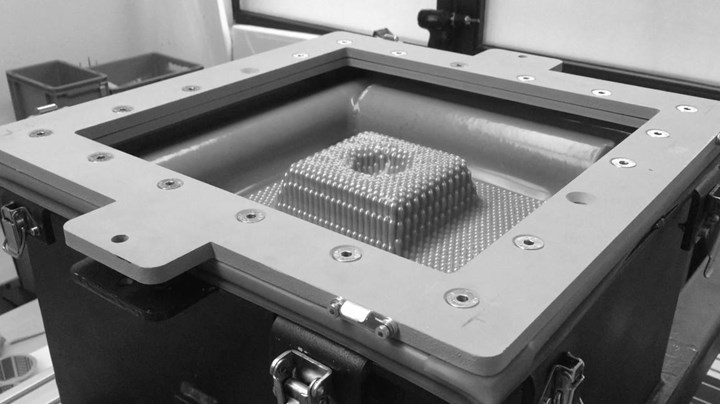

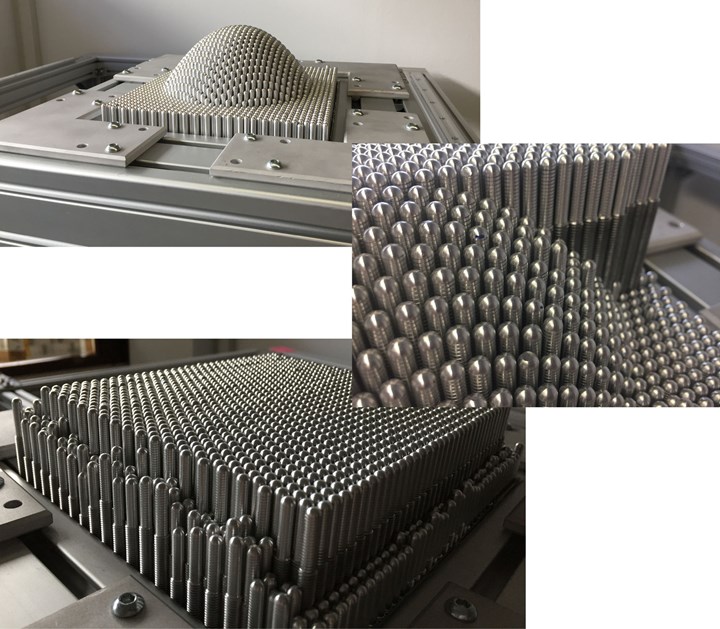

Nezami explains that because Adapa’s main applications are architecture and thermoforming glass, plastic and foam, they are producing bigger geometries and more continuous curves. “Compared to DYNAPIXEL, they use a smaller number of larger-sized actuators. Between these, the surface is interpolated and molded using a silicone sheet on top. Our system can produce sharp corners and more complex geometries. We also use a different estimation method. So, which technology fits depends on the application.”

Nezami points out that DYNAPIXEL also uses a silicone membrane, which can be used as a laminating surface and with molding processes up to 180°C. For double-diaphragm forming, you would enter the CAD data, let the software actuate the mold geometry, apply vacuum to drawn down the silicone surface on top, laminate the composite plies, close the matched mold with second membrane and complete cure.

For composite parts production, DYNAPIXEL uses a silicone membrane as a laminating surface for molding processes (e.g. double diaphragm forming) up to 180°C.

“We have a golfball-type surface texture, but using a thicker membrane will alleviate this,” he adds. CIKONI uses three membrane thicknesses: 0.5, 1 and 3 millimeters. “The thickest gives a smoother surface but less detail,” Nezami observes, “while the 0.5-millimeter membrane gives a more accurate realization but a lower-quality surface finish.”

Surface finish has not been a driving issue because DYNAPIXEL was developed as a tool to speed R&D. “Our goal was to produce additional molds and design iterations without much additional cost,” says Nezami. “Once you freeze the part design, you would then switch to CNC-machined metal molds. You can also use this as a preforming tool.”

New applications

CIKONI is now developing additional uses for DYNAPIXEL, including flexible automotive jigs for bonding/adhesive joining and production of tailored, individualized helmets and protective apparel/structures. It also has an R&D project for customized orthotics. “We see value for this type of reconfigurable tooling where you need shapes tailored to each patient,” Nezami says. “Connection to the human body must match precisely to avoid irritation and sores. There is a lot of R&D into 3D printing for this type of application, but typically the material costs are high. Using DYNAPIXEL, you can significantly cut molding costs for individualized parts.”

To learn more about DYNAPIXEL, visit CIKONI at JEC World 2020 (Mar 3-5, Paris, France) in Hall 6, N72.

Related Content

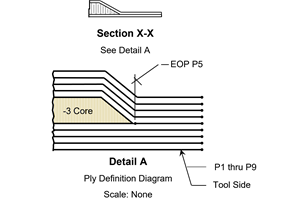

The basics of composite drawing interpretation

Knowing the fundamentals for reading drawings — including master ply tables, ply definition diagrams and more — lays a foundation for proper composite design evaluation.

Read MoreAutomated robotic NDT enhances capabilities for composites

Kineco Kaman Composites India uses a bespoke Fill Accubot ultrasonic testing system to boost inspection efficiency and productivity.

Read MoreActive core molding: A new way to make composite parts

Koridion expandable material is combined with induction-heated molds to make high-quality, complex-shaped parts in minutes with 40% less material and 90% less energy, unlocking new possibilities in design and production.

Read MoreATLAM combines composite tape laying, large-scale thermoplastic 3D printing in one printhead

CEAD, GKN Aerospace Deutschland and TU Munich enable additive manufacturing of large composite tools and parts with low CTE and high mechanical properties.

Read MoreRead Next

“Structured air” TPS safeguards composite structures

Powered by an 85% air/15% pure polyimide aerogel, Blueshift’s novel material system protects structures during transient thermal events from -200°C to beyond 2400°C for rockets, battery boxes and more.

Read MoreVIDEO: High-volume processing for fiberglass components

Cannon Ergos, a company specializing in high-ton presses and equipment for composites fabrication and plastics processing, displayed automotive and industrial components at CAMX 2024.

Read MoreAll-recycled, needle-punched nonwoven CFRP slashes carbon footprint of Formula 2 seat

Dallara and Tenowo collaborate to produce a race-ready Formula 2 seat using recycled carbon fiber, reducing CO2 emissions by 97.5% compared to virgin materials.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)