We're going to need a lot of propeller blades

As advanced air mobility expands and annual shipsets get into the thousands, the demand for composite propeller blades is expected to skyrocket. What are the implications for the composites supply chain?

Share

Read Next

CompositesWorld Senior Editor Ginger Gardiner recently paid a visit to Dowty Propellers in Gloucester, U.K. You can read about what she found there in her report, “Plant tour: Dowty Propellers, Gloucester, U.K.” found in the August 2022 issue. You will likely come away from the story impressed, as I was, about the materials and process development Dowty has done over the years to produce propellers for myriad defense and commercial aircraft engine programs.

As I finished reading Ginger’s story, and as I considered how technically challenging it is to manufacture reliable, high-performing composite propeller blades, I started thinking more about the advanced air mobility (AAM) market. As you probably know, the aircraft being developed for this air taxi market all share similar features: They are battery-powered electric, take off and land vertically, seat three to six people, are composites-intensive and, most significantly, they are powered by motors that turn propellers.

Let’s consider what these AAM aircraft might demand of the composites manufacturing supply chain just for propeller blades.

And it’s not just a few propellers. Consider the companies at the top of the AAM Reality Index (companies most likely to put aircraft into service), the aircraft they are developing and then how many composite propeller blades these aircraft require. Here are some of the leading AAM developers and the number of blades their craft uses: Archer (42), Volocopter (36), EHang (32), Joby (30), Vertical Aerospace (28), Wisk (24), Beta Technologies (11). That’s 203 blades, from just seven OEMs.

Also, keep in mind that AAM aircraft will be flying regularly over urban areas, so a rotor or blade failure, ideally, would be compensated for by redundancies in the remaining rotors and blades and not prove catastrophic. On top of that, the proximity of AAM aircraft to large populations is putting pressure on the OEMs to design blades that minimize aircraft noise.

Let’s consider now what these AAM aircraft might demand of the composites manufacturing supply chain just for propeller blades. Forecasts of the AAM market say that initial entry into service for the leaders will be 2024-2026, with limited service in a few cities globally. Annual shipset production for any single OEM during this time will almost certainly be in the low hundreds. Let’s be conservative/realistic and predict that by 2027 our seven OEMs will, all together, produce 300 aircraft per year. If you take the total number of blades they require (203) and multiply by shipsets (300), you get demand for 60,900 composite blades (not including spares).

Now, circle back to Ginger’s tour of Dowty Propellers. Dowty, arguably one of the best and most prolific large-blade propeller manufacturer in the world, has produced 25,000 blades in the last 38 years — less than half of the total blades required in the AAM estimate I just outlined above, which captures just seven OEMs in the market.

You can see where this is headed. We will very likely have to develop, in just a few years, a supply chain capable of manufacturing high-quality, durable, affordable composite propeller blades at orders of magnitude greater than the industry has ever produced. And that’s just for the initial entry into service. If AAM expands as the OEMs hope and annual shipsets reach the thousands, demand for composite blades will quickly approach half a million.

The implications here are vast, ranging from carbon fiber supply and blade design engineering to automation and product certification. Further, each OEM’s blade design is unique in size and shape, which means M&P for each blade likely will be similarly unique, at least initially, until standardization sets in.

So, can we do this? Yes. Will it be difficult? Yes. It will require substantial and expensive R&D, as well as process development and automation on a scale that we have not yet seen. The result, however, would be the creation of a new composites manufacturing segment industrialized in a way that we have only dreamed about until now.

Related Content

Alef Aeronautics earns FAA approval to launch flying car

FAA certifies testing of California startup Alef’s all-electric composite vehicle, which is drivable on public roads and has VTOL capabilities.

Read MoreComposites opportunities in eVTOLs

As eVTOL OEMs seek to advance program certification, production scale-up and lightweighting, AAM’s penetration into the composites market is moving on an upward trajectory.

Read MoreCollins Aerospace to lead COCOLIH2T project

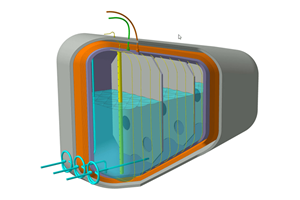

Project for thermoplastic composite liquid hydrogen tanks aims for two demonstrators and TRL 4 by 2025.

Read MoreComposites end markets: Automotive (2024)

Recent trends in automotive composites include new materials and developments for battery electric vehicles, hydrogen fuel cell technologies, and recycled and bio-based materials.

Read MoreRead Next

New Hartzell Propeller director leads the way for advanced air mobility

Mitch Heaton, director of business development and new technology will further the company’s involvement in delivering composite propellers for eVTOL, eSTOL, electric, hybrid and hydrogen aircraft.

Read MoreAll-recycled, needle-punched nonwoven CFRP slashes carbon footprint of Formula 2 seat

Dallara and Tenowo collaborate to produce a race-ready Formula 2 seat using recycled carbon fiber, reducing CO2 emissions by 97.5% compared to virgin materials.

Read MorePlant tour: Daher Shap’in TechCenter and composites production plant, Saint-Aignan-de-Grandlieu, France

Co-located R&D and production advance OOA thermosets, thermoplastics, welding, recycling and digital technologies for faster processing and certification of lighter, more sustainable composites.

Read More