3D printing is missing the third dimension

Emerging processes like continuous fiber manufacturing, in-situ consolidation and tool-less manufacturing are bringing composite 3D printing into the third dimension.

Composites manufacturing is inherently an additive process and has always been about structural efficiency in our three-dimensional world1. However, the 3D printing community has been slow to catch on. For more than 30 years, 3D printing has been stuck in 2.5D, building parts a layer at a time on a flat (2D) base to form a 3D structure with little strength in the third dimension. This Z direction weakness has been known since the 1980s, but little has been done to address it. However, 3D printing has caught the public's imagination and grown to a US$7 billion/year industry. This success is primarily due to incredibly resourceful young minds that have leapt over many of the hurdles presented by these early 2.5D technologies. But they neglected the third dimension.

Enter composites

These early rapid prototyping technologies have evolved into additive manufacturing (AM) — not just prototypes, but functional parts in real-world structural applications. The composites community has been doing this since the beginning, but we are progressing from hand layup to automatically “printing” composite structures. Automated fiber placement (AFP) was a huge step forward and is a process that is now widely used to place continuous fibers precisely where they are needed in the direction of the load paths to manufacture high-performance, three-dimensional structures. The Boeing 787, Airbus A350 and Lockheed F-35 are good examples of structures that feature composite parts produced via AFP. However, AFP with thermoset prepreg still requires a manually placed bag and an autoclave cure step, and is therefore is not considered true additive manufacturing.

Innovators like Stratasys and Markforged have added chopped and continuous fibers, respectively, to their 2.5D printers to significantly improve properties in two dimensions, but the third dimension is still lacking.

Evolving a third dimension

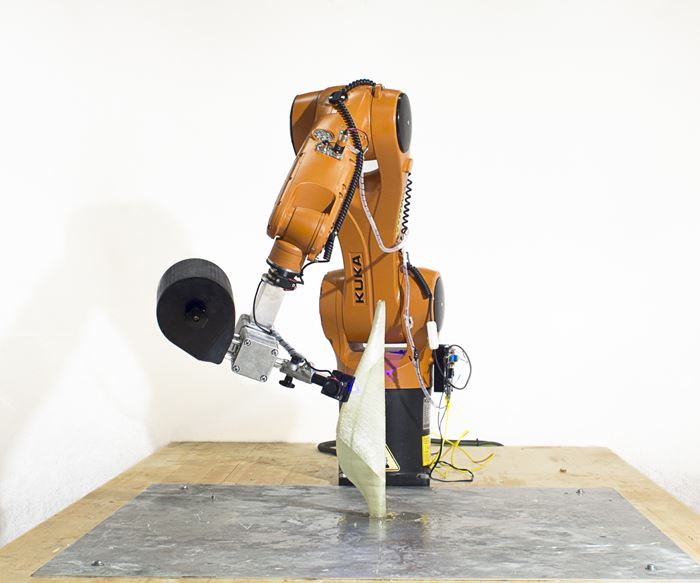

Finally, after all these years, the 3D printing community is realizing that it neglected the third dimension. Stratasys created its RC3D (Robotic Composite 3D) technology, extending fused deposition modeling (FDM) with extruded, chopped fiber-filled thermoplastics into three dimensions by using articulated arm robots2. Putting low-strength chopped fibers in the direction of load paths, as the RC3D does, is an improvement, but what about high-performance, continuous-fiber reinforcement? Arevo and moi composites3 (see photo) are doing just that — placing continuous fibers in three dimensions using advanced robotics and creative variations on the FDM theme to print high-performance 3D composite structures.

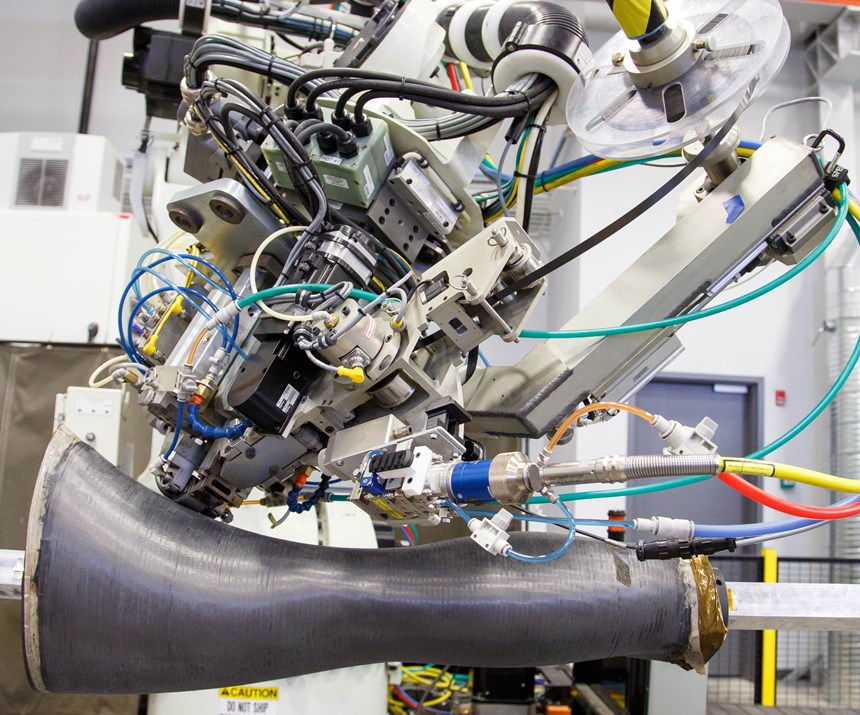

Adjacent to the 3D printing community, a small but growing group of researchers has been developing in-situ consolidation (ISC) of thermoplastic composites (TPCs). The goal from the beginning has been additive manufacturing with continuous fiber-reinforced TPCs. The 3rd dimension was always critical to the goal of high-performance ISC structures, and Automated Dynamics has employed ISC to manufacture high-performance TPC parts in serial production for more than 30 years (see photo). Finally, after all these years, AM and ISC are converging on optimal processes and structures.

Optimizing structures

Human beings are amazing creatures (most of us anyway) that have evolved over billions of years. I can't wait that long for our industry to evolve. Fortunately, we can take nature’s most important algorithm and accelerate it using computers instead of genes. Diversify-select-replicate-repeat can be performed billions of times a second using modern computers and genetic algorithms to find optimal solutions. This is exactly what is done in topology optimization and generative design to optimize structures for maximum strength with minimum weight4. It is fascinating to watch this process as structures evolve from the blocky-looking parts we are used to being produced through subtractive processes (like CNC machining) to the more organic structures produced through AM. The real beauty of this is that it is less expensive to make these optimized structures with AM because complexity is free — meaning, with more complex shapes, less material is printed, so it takes less time and materials to print a topology-optimized structure. Automated Dynamics and others are using this technology for tools, cores and even composite structures.

Tool-less manufacturing

Better yet, why not eliminate the tooling and print composite parts in free space? This is the goal of the tool-less composites fabrication process being developed by General Atomics5. The idea is to use one robot to place the composite material with FDM or ISC and another, synchronized robot to act as the tool to form a structure in free space. This technology is in its infancy, but is clearly a preview of what the future could look like for composites manufacturing.

The future

Yogi Berra once said, “It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future.” However, what I can predict is that innovative young minds will build on the formidable foundation we have constructed and create composite structures that we can't even imagine today. I can't wait.

NOTES/REFERENCES

1 Physicists prefer four dimensions and string theorists use 11 dimensions; the rest of us are stuck with 3D

2 blog.stratasys.com/2016/08/24/infinite-build-robotic-composite-3d-demonstrator/

3www.compositesworld.com/blog/post/continuous-fiber-manufacturing-cfm-with-moi-composites

4 www.compositesworld.com/blog/post/generative-design-and-continuous-3d-fiber-deposition

5 patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/a9/e5/50/0121ebc8ee29a1/US20180257305A1.pdf

Related Content

PEEK vs. PEKK vs. PAEK and continuous compression molding

Suppliers of thermoplastics and carbon fiber chime in regarding PEEK vs. PEKK, and now PAEK, as well as in-situ consolidation — the supply chain for thermoplastic tape composites continues to evolve.

Read MorePlataine unveils AI-based autoclave scheduling optimization tool

The Autoclave Scheduler is designed to increase autoclave throughput, save operational costs and energy, and contribute to sustainable composite manufacturing.

Read MoreIndustrial composite autoclaves feature advanced control, turnkey options

CAMX 2024: Designed and built with safety and durability in mind, Akarmark delivers complete curing autoclave systems for a variety of applications.

Read MoreVIDEO: One-Piece, OOA Infusion for Aerospace Composites

Tier-1 aerostructures manufacturer Spirit AeroSystems developed an out-of-autoclave (OOA), one-shot resin infusion process to reduce weight, labor and fasteners for a multi-spar aircraft torque box.

Read MoreRead Next

Developing bonded composite repair for ships, offshore units

Bureau Veritas and industry partners issue guidelines and pave the way for certification via StrengthBond Offshore project.

Read MoreAll-recycled, needle-punched nonwoven CFRP slashes carbon footprint of Formula 2 seat

Dallara and Tenowo collaborate to produce a race-ready Formula 2 seat using recycled carbon fiber, reducing CO2 emissions by 97.5% compared to virgin materials.

Read More“Structured air” TPS safeguards composite structures

Powered by an 85% air/15% pure polyimide aerogel, Blueshift’s novel material system protects structures during transient thermal events from -200°C to beyond 2400°C for rockets, battery boxes and more.

Read More