Episode 42: Jeff Sloan, CompositesWorld

CW publisher and brand V.P. Jeff Sloan discusses the history of CW and the evolution of the composites industry during his time as editor.

Jeff Sloan. Photo Credit: CW

This episode of CW Talks coincides with the 30th anniversary of the CompositesWorld brand. The first issue of High-Performance Composites, one of two magazines that would eventually merge into CW magazine, debuted in September of 1993. As part of CW’s anniversary celebration, we sat down with CW publisher and brand vice president Jeff Sloan to hear about the history of the magazine, its place in the industry and some of the industry milestones of the past few decades.

Read an excerpt:

CW: You’ve been reporting for CW for 17 years. Would you mind talking about your introduction to the CompositesWorld team and what was happening in the industry at that time?

JS: I actually started in the plastics industry out of college in 1990. So that was my very first job out of college, I worked for a new product tabloid called Plastics, Machinery and Equipment magazine. And that was my first foray into publishing in the plastics industry. That's kind of where I got my feet wet. That actually laid a lot of the groundwork for what eventually became my job with CW.

So I had that plastics industry job for a while in the early 90s, went off and did some other stuff. And then in 1996, came back to the plastics industry. When Injection Molding magazine was launched, it was launched by people I used to work with, back when I had that first job. And so I did that for 10 years in the plastics industry. Injection molding kind of reigned supreme — it’s the most used plastics processing method and I really enjoyed that work. IM magazine was a fantastically successful magazine. I learned a lot from that magazine about how to how to serve an audience, how to serve readers, what makes good content, how to develop content — and it was just a great kind of training ground for me. I eventually became editor of IM, and then eventually became publisher.

In that time, I stayed in touch with some of the other people I had worked with back in the early 90s. One of them was Judy Hazen. At the same time as IM magazine was being launched, [Hazen] had launched her own brand, which is called CompositesWorld. And the her first magazine under the composite world brand was High-Performance Composites, which as you just noted, she launched in September of 1993. I’d kind of kept in touch with her over the years, just socially and kept up to speed with what she was doing. By 2006, Judy was kind of interested in potentially selling the composites world brand and wanted to explore opportunities to do. At the same time, she had the she had two titles, she had the publisher title and the editor title, and that was that was kind of verboten. So she needed an editor. So she asked me to join her as editor in 2006, which I did.

When I came to the composites industry I thought there’d be a little overlap between you know, traditional injection molding extrusion and plastics processing and and composites manufacturing, and technically, there was a little bit of overlap. But what I found was a very, very, very different world from what I was used to in the injection molding world. Plastics processing, for those who don't know, is a highly commoditized process. Margins are super thin, everything is high speed — inject, cool, eject part, start all over. It’s a very automated machine-driven, capital-intensive manufacturing process.

I came to the composites industry, and suddenly we’re talking about laying up by hand. We’re talking about maybe a little bit resin transfer molding (RTM) and some other processes that use machinery — but this is not a machinery-dominated industry the same way plastics processing is. So, I had a huge learning curve when I came in. And on top of that, it was thermoset materials. It wasn’t thermoplastics — or at least not, not on the scale that thermoplastics are used in injection molding. And so, I had probably two or three years of drinking from the firehose, and just trying to understand what composites are, what composites manufacturing is, and what the markets are like, what the expectations are, what the processes are the tooling, the materials. You had all these fibers, all these resins, all this tooling, something like 10 different processes through which you can make a composite part. So it was just a big learning curve, for me was super, super interesting, and I really, really enjoyed those first few days of learning what this industry was like. But it was definitely a learning curve.

CW: I want to talk a bit about the time when you you really got going with magazine, the two magazines that started out High-Performance Composites and Composites Technology were launched during a time when there was a lot of R&D work happening, especially with regard to use of composites materials in aerospace and several commercial aerospace programs came to redefine basically how planes were made. I’m sure we could talk across several podcasts about some of the work that was going on at that time, but I’d like to just hear your perspective about what it was like covering the industry during that time.

JS: I came to CW in 2006. Like you said, at the time, we actually had two magazines. So the magazine that launched CW was HPC. And as the title implies, it focused on high-performance applications. That meant mostly carbon fiber in high-performance applications and markets: aerospace defense, a little bit about automotive racing, and a little bit of automotive.

Then Judy eventually created a second magazine called Composites Technology, and that was designed to cover the rest of the composites industry. So basically anything not carbon fiber, and not high-performance. So, that included wind and marine and industrial applications and things like that, and a lot of glass as well classified replications. We kind of lived in these two worlds, and each magazine was published six times a year. So one month, you’re working in this high-performance applications world, and then the next month, you’re working in this non-high-performance applications world.

For a long time, it made sense to think of the industry that way, because the applications were so different. But over time, it became more and more difficult to segregate the industry that way. Take, for example, the wind energy industry — wind blades for a long time, were relatively short and glass fiber. But as wind blades got longer, you know, there was a need to add carbon fiber, particularly spar caps into the wind blades. And as that started to happen, it became harder for us to say, “okay, we’re only going to cover wind blades in CT.” Because we’re adding all this carbon fiber and these structures are actually becoming high-performance structures. So then how do you how do you decide if a wind blade story goes in one magazine or the other. At the same time, we started seeing more carbon fiber going into the marine industry, particularly in large structures. Do again, do we treat that as a high-performance structure? Or is it just a is it a non-high-performance structure. In the automotive industry, we’d start to see more carbon fiber going into cars, it wasn’t just glass fiber anymore. And so it was harder and harder for us to make that distinction.

So, we eventually joined the two magazines together to create CW.

It was kind of an interesting time in the industry because we were at this odd inflection point.In 2006, the Boeing 787 had been announced and it was said that it was actually in early production. It was in July of 2007, that the first 787 Rules rolled out in Everett, Washington — it was televised. But it was kind of it was kind of a ruse because the plane had no avionics and had no interiors. I think the engines were not really real. The wing engines were definitely not real engines. But it was just basically a carbon fiber composite aircraft structure with nothing in it. They rolled it out just to show that they had built the first 787.

Then Boeing made a lot of promises about how they were going to start test-flying the aircraft — I think they were going to plan to do it by the end of 2007. If you just go back and look at the history, you’ll see that that didn’t happen. Then they said they were going to push the first flight out to early 2008. And then that didn’t happen. They had delay after delay after delay. And a lot of the delays were just normal, building it for aircraft for the first time delays.

It wasn’t until late 2009 that the 787 flew for the first time. And that was kind of a pretty big milestone in the industry, to my way of thinking, you know, represented a huge leap in carbon fiber application and aircraft structure. And seeing that plane fly for the first time was really amazing. There was a great sense of pride for the industry in terms of what you know, what can be accomplished with large carbon fiber structures in a certified aircraft.

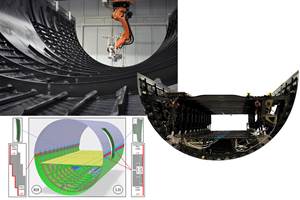

Soon after the 787 was certified and then began deliveries and the plane went into service, on the heels of that came the Airbus A 350 — a very similar aircraft, very similar use of materials, but very, very different manufacturing processes. And so you know, Airbus came at this at 350 in a different way than Boeing did with the 787, but two very similar aircraft and using the materials in a similar way. These two aircrafts are to me are like kind of like signposts in terms of the evolution of the composites industry, because they represent such a big leap in terms of volume and value and application. It was really good to see that this material can be applied in that way. And I think it gave the industry a lot of confidence and proved what can be done.

The other thing was when I came in at the end, when I came into CW in 2006, a lot of the stories we were writing were about replacing metals in existing applications. So a lot of the industry grew up trying to prove composites’ value by saying: “Look, you’re making this structure out of aluminum right now, but if you make it out of carbon fiber, or glass fiber, or whatever — whatever the application is — if you use this, you’re going to save weight, and you’re going to actually improve your strength properties. It’s going to be more durable. There’s all these benefits.” So very often the material was replacing an existing non-composite material in an existing partner structure application. We call that “earning our way into programs” or “earning our way into structures.” We were always trying to prove composites’ capabilities in these applications. So we want to displace some metal. That was always the first opportunity: “Can we convince somebody to let us displace this metal and replace it with this better composite structure?”

But what I think is happening now — and this I think this kind of started with the 787 and A350 — we started realizing that we don’t have to replace things, we can be the material. We have a lot of markets evolving today and we have a lot of applications coming out where composites are not replacing and they are not just an option, they are like the only option or they’re the best option. And so in that way, they're kind of an enabler.

A good example of this is advanced air mobility, where you got these aircraft are powered by batteries and electric motors, you have to have composites on those aircrafts to make the value proposition work for those manufacturers. Aluminum is not an option. No other material is option. It has to be composites.

The same is true, I would say for hydrogen storage. I think composites are by far the best material option when it comes to building pressure vessels for hydrogen storage. And so we're not replacing existing material, we’re saying that this is the very best option for doing what you need to do. And so for a lot of these markets to exist, they have to have composite materials. Where we used to have this kind of specialty environment where we’re replacing things, we are now the primary material option, the primary material of choice. And I think that I think that’s starting to change the mindset of OEMs in particular, and even suppliers within the industry. They’re changing how they view the industry and how they, how they respond to different market signals. So, it’s a really interesting time. And all that has happened over the last 17 years —that’s been a big change since the 787 and A350 were developed.

Related Content

ASCEND program update: Designing next-gen, high-rate auto and aerospace composites

GKN Aerospace, McLaren Automotive and U.K.-based partners share goals and progress aiming at high-rate, Industry 4.0-enabled, sustainable materials and processes.

Read MoreWelding is not bonding

Discussion of the issues in our understanding of thermoplastic composite welded structures and certification of the latest materials and welding technologies for future airframes.

Read MorePlant tour: Joby Aviation, Marina, Calif., U.S.

As the advanced air mobility market begins to take shape, market leader Joby Aviation works to industrialize composites manufacturing for its first-generation, composites-intensive, all-electric air taxi.

Read MoreManufacturing the MFFD thermoplastic composite fuselage

Demonstrator’s upper, lower shells and assembly prove materials and new processes for lighter, cheaper and more sustainable high-rate future aircraft.

Read MoreRead Next

Episode 39: Joe Fox, FX Consulting

Consultant Joe Fox talks about the massive potential for composites use in infrastructure applications and what it will take to turn that potential into reality.

Read MoreEpisode 40: Sarah Cox, NASA

Sarah Cox, materials engineer at NASA, talks about her experience at NASA working with composites in the space travel space.

Read MoreEpisode 41: Chase Hogoboom, T.J. Perrotti, Composite Energy Technologies Inc.

Chase Hogoboom (president) and TJ Perrotti (senior Naval architect and chief design engineer), CET Photo Credit: Composite Energy Technologies Inc.

Read More