Cast polymer market: On the upswing

Postrecession, this commodity industry is emerging stronger and going global as competitive pressures encourage innovation.

The global demand for cast polymer materials used in residential and commercial construction is substantial. According to a recent study by the Freedonia Group (Cleveland, Ohio), the cast polymer market is forecast to grow by 8.1 percent per year, to 263 million m2 (2.83 billion ft2) per annum by 2016, with more than half the demand attributable to Asia (especially China). Market gains will be boosted by growth in the U.S., in both its new housing and remodeling sectors, as well as expansion expected in Europe, Australia and Japan, says Freedonia.

In 2016, kitchen and bath countertops are expected to account for 86 percent of cast polymer demand. Although new housing starts will provide the most rapid gains, the majority of the demand, says Freedonia, will come from home remodeling and institutional projects, such as hospitals and schools. In the U.S., the National Kitchen and Bath Assn. (NKBA, Hackettstown, N.J.) reports that cast polymer surfaces continue to be key kitchen and bath components, and their share in each sector is trending upward in competition with granite and engineered stone.

This remarkable uptrend, however, comes on the heels of what industry veteran Charles Martin, a sales manager at resin supplier CCP Composites (Kansas City, Mo.), calls “a perfect storm” that hit manufacturers since CT last covered this topic (see the titles lsited under “Editor's Picks,” at top right). It began in the late 1990s, when attractively priced natural granite began to flood the market from China, Italy, India and other sources. New methods for economically mining, cutting, polishing and edging this previously luxury surface had driven its price down significantly. Meanwhile, more aggressive ceramic tile and high-pressure laminate industries touted their wares to consumers and builders. What’s more, cast polymer manufacturing in Asia, Mexico and elsewhere brought a slew of low-cost imports to U.S. home improvement stores during a time when raw material prices for domestic users of resins and fillers were increasing. Then came the collapse of the long-reliable U.S. housing finance market in 2007, a major impetus for the global recession.

Caught up in these events, only 700 of 1,200 U.S. cast polymer companies survived. “The challenge, particularly for cultured marble firms, was that the historical cost advantage went away when low-cost granite and imports entered the market,” says Bob Moffit, senior product manager at Ashland, LLC (Dublin, Ohio), a key cast polymer resin supplier. “Consumers could get granite — a perceived high-end material — at a price point similar to cast polymer products.”

Now in its sixth decade, the industry appears to be turning the corner. A hygienic alternative to porous natural stone, cast polymer can be customized and is now available in green formulations. Cast polymer materials offer huge design flexibility for wheelchair-accessible and more-easily cleaned kitchens and bathrooms, an aid to Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliance. And although the basic technologies remain the same (see “Cast polymer categories,” at the end of this article or click on its title under "Editor's Picks," at top right), leaner practices, new materials and processes, new markets and new marketing methods are driving the latest resurgence. Says Martin, “Many companies have completely changed the way they do business to adapt to today’s conditions.”

Jack Simmons, VP at filler manufacturer ACS International (Tucson, Ariz.) sums up, “I think the industry is at the end of the latest down cycle. The goal now is to continue to create differentiated products that stand out, to compete with natural stone and tile.”

A better business model

The players in the far-flung and fragmented cast polymer industry range from global solid surface giants like DuPont (Wilmington, Del.) to local, two-person shops. As the foregoing indicates, many companies have had to adapt to changing conditions — or reinvent themselves. “I think the industry was coasting through the 1960s and 1970s, since business was good and costs were low,” says Anne Morris, a former board member of the International Cast Polymer Assn. (ICPA, part of the American Composites Manufacturers Assn., Arlington, Va.) and a technical sales representative at distributor Composites One (Arlington Heights, Ill.). “After the big downturn in 2007, companies for the first time had to think about their business strategy, and had to do more with less and become more cost-effective.”

“We weathered the storm because we chose to diversify,” says Peter Martin, director of administration, marketing and information technology at solid surface manufacturer Tower Industries (Massillon, Ohio). “We went from producing slabs and engineered composites to working with architects, designers and contractors, and directly with consumers.” In addition to producing solid surface sheets, using a proprietary resin formulation and R.J. Marshall Co., The (Southfield, Mich.) fillers, Tower offers custom fabrication and installation for residential remodelers, kitchen and bath dealers, new-home builders and large institutional customers. The company also offers its customers a choice of surfacing options, including granite and engineered stone. According to Martin, Tower’s college and university business — which includes solid surface vanity countertops, lavatories and shower bases/enclosures — is projected to more than double in volume this year. Institutional contracts are helping to drive the company’s current robust growth.

Mobile Marble (Mobile, Ala.), a small, family-owned engineered composite fabricator headed by David Lindsey, transformed itself into a bath remodeling firm, offering renovations directly to customers, in a range of materials, including engineered composites. “We made so much white cultured marble in the 1990s that the product just became boring, especially for new construction. We have a design showroom now, and customers come to us to pick out their materials, whether it’s just a new vanity top or a complete bathroom with a tub replacement shower,” explains Lindsey. “If someone wants engineered composites, we can still make the part directly, in their choice of color, using our molds and materials.” He adds that having the TruStone product line (described in next section) “saved our business. We can now do a complete bathroom install and make it look like real stone, but without the drawbacks of stone.”

Another firm that successfully switched focus is Monroe Industries (Avon, N.Y.). The company specializes in customized shower enclosures and now works with kitchen and bath designers and has its own design showroom. Monroe also offers complete bath installations — a far cry from the firm’s business plan in the 1980s. “We are not your grandmother’s cultured marble,” quips Monroe’s vice president, Bonnie Webster.

ACS’ Simmons explains, “Cast polymer manufacturers needed to change their marketing approach. They can no longer sell only new-home construction, or to consumers who happen to come into a showroom at their manufacturing facility. Consumers find multiple options, using the Internet, and simply won’t travel very far to industrial areas.”

Morris points out, “The key is an ability to customize shapes, whether for bowls, countertops or showers, giving shops the ability to better compete today.”

Engineered composite and solid surface firms that weren’t dependent on residential new home construction had it better, but they still suffered during the downturn, according to Bradley Corp.’s (Menomonee Falls, Wis.) senior marketing manager, Kris Alderson, whose company also had to diversify its product lines. Bradley had previously supplied only commercial customers, and its well-known Bradleys, or circular washbasins with multiple taps that can accommodate several people at once, were originally done in terrazzo when they were introduced in 1920.

“About 20 years ago, we started migrating to cast polymer, and now make most of our products from solid surface or our own engineered stone product. It’s more durable than gel-coated engineered composite for our customers’ institutional settings,” adds Alderson. The company has a large product development program to innovate and anticipate trends, which helped it during the recession. For example, its award-winning Advocate All-in-One is an innovative, complex-shaped, wall-mounted solid surface washroom sink that provides soap, water and hand drying in one unit. Cameron Barnes, Bradley’s materials engineer, says the solid surface part is molded as one piece in a proprietary mold made in-house by Bradley engineers.

Another major engineered composite player, Mincey Marble (Gainesville, Ga.), left the residential market behind in the mid-1990s, says Natt Davis, director of business development. Mincey moved into health care, military housing and educational institutions and now claims to be one of the largest providers of engineered composites to the hospitality industry.

The company realized early on that it is better to make hundreds of parts from one mold than to cast one-off custom parts, adds Davis. Mincey supplies trademarked MINCOR tub and shower panels that achieve a Class A rating per ASTM International’s (West Conshohocken, Pa.) E84 tunnel test, thanks to a specific ratio of raw materials and additives. The panels meet hotel building code standards. Its antimicrobial solution incorporates Agion-branded antimicrobial technologies into a number of products for health care and other germ-averse customers. Together these innovations have helped Mincey expand — it just added 30,000 ft2 (2,787m2) of manufacturing space to accommodate increased demand.

Getting image-conscious

Because natural granite continues to be a formidable competitor, cast polymer manufacturers are embracing ways to make engineered composites look exactly like granite through imaging techniques. Photofuzion, a patented technology developed by TruStone Products LLC (Bluffdale, Utah), can imprint or embed a high-resolution photographic image, using heat and pressure, into the gel-coated surface of an engineered composite slab within minutes. Images can include granite, marble, travertine and virtually any other textured material. “Our graphics department has even set up images of branded leather for a Wyoming homeowner,” quips TruStone’s president, Doug Tibbitts.

How does it work? Tibbitts explains that after a fabricator manufactures, cures, demolds and finishes a composite slab, the slab is moved into the Photofuzion heat press; a granite image, on paper printed with “a dye sublimation ink in an unstable state,” is placed over the slab, then the slab is enclosed within the press. When vacuum and heat are applied, the ink sublimates, that is, it transforms to a gaseous state, and the vacuum drives the gas into the gel coat. “While it can’t be used for bowls or highly curved parts, the image can be transferred to gentle edge radii or even shower bases,” says Tibbitts, who adds that the images set up by his firm are compatible with most gel coats. A gel coat thickness from 18 to 22 mils works best, and technicians need to watch variations in thickness along slab edges, which can affect the image.

Not only are TruStone parts doppelgängers for granite, the heat cycle helps postcure the gel-coated slabs, which improves finished part durability. Charles Martin adds that CCP Composites offers STYPOL acrylic-modified gel coat (CCP 4917) that has been optimized for the Photofuzion process.

Mobile Marble’s Lindsey, a TruStone Photofuzion licensee, says virtually all of his engineered composite parts are now made with the process. “It looks like stone, no question — this process really helped our business survive when real granites, marbles and tile were the trend.” He points out to his customers that granite makes no sense in a bathroom, because of its weight, porosity and cost. With his product, they get an identical look that’s water- and mildew-resistant, easier to clean, has no grout lines and doesn’t require sealing. His sentiments are echoed by other TruStone licensees, including Venetian Marble Co./Ortega Kitchen and Bath (Lubbock, Texas) and Lighthouse Marble (Biloxi, Miss.). Nearly 70 other engineered composite manufacturers have licensed the process in the past five years.

Another image-transfer technique is offered by Tyvarian (Lindon, Utah), headed by president Jeff Hall. “We can replicate natural surfaces like granite and marble but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. We can transfer not only photos but digital art, patterns, logos, and more — ideas that were never possible before,” says Hall. “We feel we’re giving designers a lot of creative options.” In the case of Tyvarian, an image is transferred into a clear polyester resin, with a thickness of ~25 mils. The relatively thick resin coat means that the image is difficult to damage, as proven by scratch and UV testing. “Scratches can be buffed out without touching the image,” says Hall. Tyvarian is investigating the transfer of patterns, like glass tiles or subway tiles, onto cast polymer panels to get the tiled look in shower enclosures and kitchen backsplashes without the drawbacks of tile’s porosity and grout lines. More than 45 Tyvarian dealers in North America have licensed the process, which, say many, helped them through the difficult economic downturn.

Synthetic stone, real value

In the more expensive realm of engineered stone (also called engineered quartz), where the goal is to closely approximate natural granite without the high cost of quarrying, cutting and shaping blocks of stone, the high capital equipment cost of the established Breton process (see the “Cast polymer categories” sidebar, below) puts it out of reach for smaller producers. Mark Harber, cast polymer business manager at AOC Resins (Collierville, Tenn.), says, “We have several customers making a lot of engineered stone with our resin, with proprietary recipes, and we’re seeing an upward trend in consumer demand, especially from consumers who delayed remodeling projects.”

“Engineered stone is growing very fast, and did even during the downturn,” contends Daryl Francis, casting group business manager at Interplastic Corp. (St. Paul, MInn.). “Because it’s a premium product, there is less cost pressure.”

Bill Schramm, director of global business development for composites at resin supplier Reichhold LLC2 (Durham, N.C.), adds that consumer demand for upgraded kitchens is a big driver, because engineered composite can’t compete in the kitchen.

But, robust demand has led some manufacturers to develop their own versions of engineered stone on a smaller scale, without the costly Breton machinery. Bradley Corp., for example, spent years developing a proprietary production method capable of making shaped bowls and parts using granite and quartz in a polyester resin. “Our process is comparable to the amount of labor needed to make solid surface,” claims Barnes, “although finishing and polishing requires more time due to the harder nature of the engineered stone.” Bradley’s nonporous Evero Natural Quartz Surface is reportedly customizable to any shape and is said to contains up to 70 percent recycled content, including shells and glass. Adds Alderson, “We’re able to work with architects to develop a higher-end look for any type of building.”

ACS International’s Simmons reports that the ICPA is supporting the trend of low-cost production of engineered stone with a research study on best practices and materials to assist small manufacturers. He states, “If this push is successful, it could really open up new markets, especially kitchens, for the small producers.”

A greener opportunity

Perhaps the biggest trend in cast polymer is the emergence of green fillers and resins, driven in part by the high prices of petroleum in 2008 and 2009, says Moffit, which made green sources more cost competitive. Used in both residential and commercial installations, the green chip is worth playing. “Builders get credits for incorporating recycled content as part of the LEED program [Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, part of the U.S. Green Building Council],” says Moffit, “and that’s very important to many builders and consumers.” But for Schramm, it’s a two-faced coin: “Bio-resins like our Envirolite polyester provide plenty of performance. The issue becomes that ‘green’ costs more, and fabricators still need to keep their costs low.” According to Moffit, fabricators have migrated away from a focus on bio-resins to incorporating more cost-neutral components, such as recycled fillers and resins containing recyclate.

Monroe’s Webster asserts that her firm pushed ahead to develop its Robal recycled postconsumer, prelandfill glass filler, for which it has won several awards. “It was a big investment, and it’s costly to clean and crush the glass, but we believe it has opened a lot of doors and brought in customers who demand green products.” Robal also is available to other producers under a licensing agreement. Monroe can achieve up to 82 percent recycled content by weight when it combines Robal with bio-resins, such as Ashland’s Envirez product line. “We pride ourselves on offering the most innovative materials and longest-lasting products,” says Webster.

Bradley’s Evero engineered stone product is also considered green, with its 70 percent recycled content. And Mincey Marble offers its customers minceygreen, a trademarked commercial line of sustainable products, with 30 percent postconsumer content, for LEED credits. Simmons reports that ACS uses postconsumer waste — recycled polyethylene terephthalate (PET) from soft-drink bottles — in its Poly Chips thermoplastic granules series — Artistone, Dura Stone and Poly Stone — with bio-resins as the binder. “Our Ecotone line uses post-consumer recycled glass and other renewable resources for LEED points, and our Terra Bella line is made with recycled gemstone waste,” he adds.

“Green building is here to stay, but it’s evolving,” observes Scott Williams, product development manager at R.J. Marshall. “Our solid surface color granules contain up to 22 percent postindustrial recycled content, and we also grind B-grade fiberglass strand for filler, which otherwise would go to a landfill.” His company’s ReStone product contains 30 percent pre- and postconsumer recycled glass combined with fillers and patented color granules, and it is eligible for LEED rating points.

“The industry has some momentum developing with builders and architects now,” concludes Moffit. “With our greater presence at architectural and builders shows, and with the compositebuild.com Web site, we’re helping specifiers better understand the value proposition for engineered composites and cast polymer surfaces.”

Related Content

CirculinQ: Glass fiber, recycled plastic turn paving into climate solutions

Durable, modular paving system from recycled composite filters, collects, infiltrates stormwater to reduce flooding and recharge local aquifers.

Read MoreHexagon Purus Westminster: Experience, growth, new developments in hydrogen storage

Hexagon Purus scales production of Type 4 composite tanks, discusses growth, recyclability, sensors and carbon fiber supply and sustainability.

Read MorePlant tour: Middle River Aerostructure Systems, Baltimore, Md., U.S.

The historic Martin Aircraft factory is advancing digitized automation for more sustainable production of composite aerostructures.

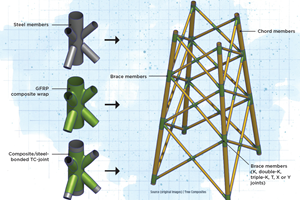

Read MoreNovel composite technology replaces welded joints in tubular structures

The Tree Composites TC-joint replaces traditional welding in jacket foundations for offshore wind turbine generator applications, advancing the world’s quest for fast, sustainable energy deployment.

Read MoreRead Next

Cast polymer concrete structures save city's sewers

Beneath its historic colonial charm, Charleston, S.C. had an underground sewer system in need of repair. Engineers at U.S. Composite Pipe (Alvarado, Texas) devised a solution that included unique cast polymer composite sewer interceptor structures — 10-ft/3m-diameter vertical access shafts that extend as far as 110

Read MoreAutomation In The Cast Polymer Industry

Material and labor savings result when manufacturers automate cultured stone and solid surface processes.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)