Bone or composite? Several of the dinosaurs on display at the Cincinnati Museum Center’s Dinosaur Hall contain a mix of fossils excavated by the museum’s paleontology team and casted bones built and mounted by Research Casting International. Source | CW

“Dinosaur skeletons are never complete.” Glenn Storrs, Ph.D., associate VP for collections and research and Withrow Farny Curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Cincinnati Museum Center (Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S.), adds that if you are able to dig up 50% or more of a dinosaur’s bones out in the field, you can build a pretty accurate restoration.

Composite materials — whose light weight, strength and other properties lend themselves to high-profile applications such as structural parts for commercial aircraft, wind turbine blades and pressure vessels for energy storage — can also be used, it turns out, to fill gaps in the fossil record. In some cases, replicas also enable museums to display their specimens to the public, while the original bones are kept behind-the-scenes for research and study.

“Back in the day — and when I say that, I mean as far back as the 1800s — museums originally used plaster of paris,” Storrs says. “It was about 40 years ago that resins came into wider use.”

For smaller bones and casts for exhibits within the museum — plants or fish, for example — museum staff use urethane foams to cast and sculpt the replicas themselves, says Dave Might, exhibits coordinator/artist at the Cincinnati Museum Center.

Almost complete. The skeleton for the Cincinnati Museum Center's Galeamopus was an almost complete skeleton, excavated by Glenn Storrs and his team. Research Casting International filled in the missing bones. Source | CW

Dinosaur bones and larger museum displays can pose a unique challenge, however. Although bones range in size, they can be massive, and any material replicating them must be light enough to be suspended in the air on a mounted display, and durable enough to last for many years. “Depending on the size of the skeleton, we may need a strong, rigid exterior surface and hollow inside,” Storrs says. He adds, “A big, heavy piece of plastic won’t work, and, frankly, wouldn’t cure properly anyway.” Composite materials, whether solid or foam-filled, are often able to fill these material needs.

Dave Might remembers the animals in the Ice Age exhibits, built decades ago for the Cincinnati museum — a mastodon, a giant bison and others, now on display at the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport — that museum staff made casts for on-site using fiberglass composites. They even produced a large, fiber-reinforced lizard once, he recalls.

More recently, though, for the dinosaurs now on display in the museum’s Dinosaur Hall, the Cincinnati Museum Center, like many museums around the world, turned to a company called Research Casting International (RCI, Trenton, Ontario, Canada) for its fossil casts.

Molding and casting composite dinosaur bones

RCI operates a 50,000-square-foot facility in Ontario, Canada, alongside a 10,000-square-foot facility to store the company’s roughly 15,000-20,000 molds from about 270 different dinosaur skeletons. The company does everything from aiding the museums in fossil digs, to molding and casting bones, to mounting the exhibits within the museums.

Making the molds. Technicians from RCI painstakingly build silicone molds of Bracchiosaurus vertebrae. Source | RCI

Matt Fair, general manager of operations at RCI, has been in the business of molding and sculpting dinosaur bones for 30 years, starting at RCI three years after the facility opened in 1987. Sometimes, Fair says, a museum just needs to fill in missing bones that were not retrieved in the field excavation, such as the case with the Cincinnati Museum Center’s Galeamopus skeleton, collected by Storrs and his team with almost 80% of fossils intact. RCI can use its vast collection of bone molds from other museum fossils to create a bone cast based on another skeleton of the same species.

Alternatively, some entire skeletons can be purchased “off-the-shelf” from RCI. “For example, take Tyrannosaurus rexes,” Fair says. “There are only about 29 or so skeletons in the world, and that’s not nearly enough for all of the museums and theme parks that want one. So we produce 100% composite T. rexes.”

Off-the-shelf T. rex. This T. rex on display at the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) is a 100% fiberglass/polyester replica built by RCI. Source | RCI

According to Fair, a typical dinosaur casting project takes about three months to complete if RCI already has a mold in stock for that species, and longer if the project requires fabrication of a new mold.

First, when needed, the company helps in the collection of fossils in the field— in addition to the casting side of its business, RCI also helps with fossil preparation and specimen storage. Then, back at the Ontario facility, the casting department makes a mold directly from the bones. Applying digital laser scanners from Artec 3D (Luxembourg, U.K.) to scan the original bone, RCI is able to create an accurate reconstruction or, depending on the need, to enlarge or reduce the part for the exhibit, create mirror-image parts, or digitally sculpt missing parts. The molds themselves are made of room temperature-vulcanizing (or curing) RTV silicone rubber, and fiberglass for the mother mold. According to Fair, the company’s 3D Systems (Rock Hill, S.C., U.S.) 3D printers are also sometimes used to create molds, or to build larger or smaller replicas.

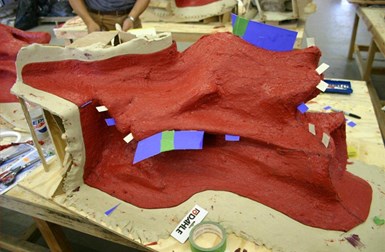

Ready for casting. The finished mold for a Bracchiosaurus vertebrae replica is made of silicone (red) on top of a fiberglass mother mold. Source | RC

Depending on the size and weight requirements for the part, RCI uses mostly fiberglass mat or roving from suppliers including INEOS (Columbus, Ohio, U.S.), Polynt (Brampton, Ontario, Canada), or Composites Canada (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), but they have also used carbon fiber for some of the largest parts that need to be the most lightweight, as well as Kevlar and other materials. Resins, often epoxy or others depending on the project, are supplied by companies including West System Inc. (Bay City, Mich., U.S.) and Smooth-On Inc. (Macungie, Pa., U.S.). The cast itself is then produced mainly via hand layup, which for some large parts, may also be vacuum-bagged; smaller parts may be made with chopped fiber dispensed via a spray gun is used. Next, the part is demolded, trimmed and set up on a metal armature alongside the rest of the skeleton. The composite designs, unlike the actual fossils, Fair says, often account for the metal frame running through the middle of the part, to hide the framing better. Finally, the part is finished with paint and gives the appearance of actual bone, and sometimes additional sculpted elements to give the appearance of skin.

Composites on display around the world

The first project Fair ever worked on was a fiberglass/polyester Allosaurus on display at the American Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C., U.S. Some of the largest projects RCI has done to date include nine all-composite replicas of “Sue,” the most complete T. rex skeleton discovered, which can be found in several museums as well as Disney World’s Animal Kingdom in Orlando, Fla., U.S.

RCI’s dinosaur casts can be found in museums globally, but the company’s work isn’t limited to museum dinosaurs, Fair says. Other projects topping his list include dinosaur replicas for the Jurassic Park movies, planetarium planets and fiberglass composite panels depicting geographical surfaces from around the world for the American Museum of Natural History. “It’s pretty neat to walk into a museum somewhere, or a theme park,” notes Fair, “and see your work on display.”

Related Content

Filament winding increases access to high-performance composite prostheses

Steptics industrializes production of CFRP prostheses, enabling hundreds of parts/day and 50% lower cost.

Read MoreReinforcing hollow, 3D printed parts with continuous fiber composites

Spanish startup Reinforce3D’s continuous fiber injection process (CFIP) involves injection of fibers and liquid resin into hollow parts made from any material. Potential applications include sporting goods, aerospace and automotive components, and more.

Read MoreASCEND program update: Designing next-gen, high-rate auto and aerospace composites

GKN Aerospace, McLaren Automotive and U.K.-based partners share goals and progress aiming at high-rate, Industry 4.0-enabled, sustainable materials and processes.

Read MoreInfinite Composites: Type V tanks for space, hydrogen, automotive and more

After a decade of proving its linerless, weight-saving composite tanks with NASA and more than 30 aerospace companies, this CryoSphere pioneer is scaling for growth in commercial space and sustainable transportation on Earth.

Read MoreRead Next

Teijin aramid, carbon fibers used for museum façade panels

The new wing of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam is the first and largest composite building constructed from Teijin’s Twaron and Tenax fibers.

Read MoreLucas Museum of Narrative Art uses GFRP base isolation system

The GFRP panels enable the building’s curvilinear shape and are lightweight enough for the base isolation system to rock in the event of an earthquake.

Read MorePlant tour: Daher Shap’in TechCenter and composites production plant, Saint-Aignan-de-Grandlieu, France

Co-located R&D and production advance OOA thermosets, thermoplastics, welding, recycling and digital technologies for faster processing and certification of lighter, more sustainable composites.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)