GE Aviation, Batesville, MS, US

With a supply chain busy making commercial jet engines like the GE90, GEnx, LEAP and GE9X, GE Aviation has invested heavily in its composites capabilities in Batesville.

In many advanced manufacturing facilities, there is a great emphasis on managing equipment and technology — much of it automated — with a secondary emphasis on the people who run such machinery. In composites manufacturing, however, especially in the aerocomposites realm, where touch labor is still integral to many fabrication operations, people are as important as equipment to timely, profitable plant operations.

That was certainly the case when CW visited Batesville, a small town of about 7,500 inhabitants located in the northern half of the US state of Mississippi, an hour south of Memphis, TN. It was here, in 2008, that GE Aviation (Cincinnati, OH, US) decided to build its latest aerospace manufacturing plant, with facilities for both composites and metals fabrication — primarily for aircraft engine applications.

The 37,161m2 plant opened in 2009 and joined the more than 80 other GE Aviation manufacturing facilities in the company’s supply chain. Like all the other facilities, Batesville shares the GE Aviation name but also operates independently. All GE Aviation plants are internally responsible for winning and keeping work and, therefore, must compete for it against not only fabricators who compete with GE but fellow GE facilities as well.

Plant manager Jackie Clark, who led CW on the plant tour, says the competitive culture instilled by GE Aviation senior leadership helps make for a robust, demanding work environment in which a premium is placed on employees who are truly vested in the work — those who have, as Clark says, “skin in the game when it comes to performance. We’re not looking for clock punchers.”

Seeing to flight-critical engine CFRP

What is GE Aviation Batesville making that requires such rigorous attention to detail? Anyone with even a passing interest in aerospace propulsion knows that GE Aviation was the first jet engine manufacturer to use carbon fiber composite fan blades, in its GE90, which entered service 21 years ago on the The Boeing Co.’s (Chicago, IL, US) original 777. It was followed, in 2006, by the even more composites-intensive GEnx, developed to power the Boeing 787 and 747-8. Next came the LEAP engine, developed by CFM International (Cincinnati, OH, US), which is a GE Aviation/Snecma (Safran, Paris, France) joint venture. And, coming soon is the GE9X, which will feature a next-generation carbon/epoxy fan blade design on board the revamped Boeing 777X aircraft (read “GE9X engine for the 777X to feature fewer, thinner composite fan blades” online under "Editor's Picks" at top right).

A host of carbon fiber composite parts, big and small, for these engines are made by a well-coached, well-developed, cohesive workforce to fabricate flight-critical parts to tight specifications.

On a very large floor

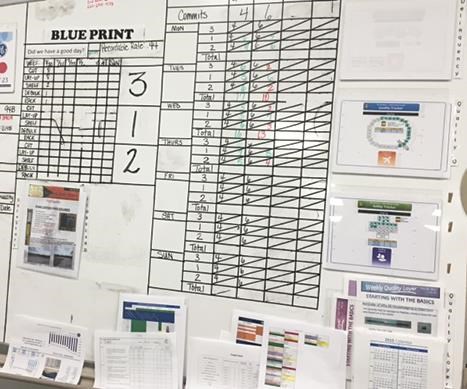

Our tour starts on the shop floor on the composites side of the Batesville facility, with an introduction to the Cell Control Center. To the unpracticed eye, it is just another bulletin board — but an important one, as on closer inspection, it maps every activity on the shop floor and exemplifies the culture of the Batesville operation. Every part manufactured at Batesville is fabricated in a team (Cell) environment in or near one of 13 modular cleanrooms. The daily performance of each Cell — cycle time, throughput, technical problems, successes — is tracked through the Cell Control Center. At 3:15 p.m. everyday, there is an assessment: All of the “coaches” (there are no “managers” in Batesville) gather at the Cell Control Center to review production opportunities (there are no “problems”) and production successes. At the Cell Control Center, and throughout the plant, the rule is simple: If you have a “production opportunity,” attempt first to solve it within your team; if that fails, escalate it to higher authorities. “A team,” says Clark, “is a good one when it regularly solves its own problems.”

Each cleanroom on the shop floor provides the same basic thing: A clean, well-conditioned environment for the hand layup of dry carbon fiber fabric preforms in preparation for resin transfer molding (RTM). The first cleanroom into which we enter is making LEAP 1B fan platforms, the carbon fiber for which is cut on a Gerber Technology (Tolland, CT, US) automated flatbed cutting table and then kitted. The kits are laid up by hand for preforming. Preforms are then loaded into a series of two-cavity tools.

The in-cavity layup for the LEAP 1B fan platform part comprises three preforms, a foam core, and another three layers of preforms. Each tool is then press-loaded, resin is injected via RTM, and the part is cured under pressure for about 5.5 hours. To ensure consistent processing, all of GE Aviation Batesville’s RTM equipment is acquired from a single source, Radius Engineering Inc. (Salt Lake City, UT, US).

There are 18 fan platforms per LEAP 1B engine, and the LEAP is being specified for the Airbus A320neo and the Boeing 737 MAX, which means CFM International will, by 2020, manufacture 1,800 LEAP shipsets per year. That engine program will put a lot of pressure on suppliers, including GE Aviation Batesville, and Clark notes that the facility’s biggest challenge will be meeting these full-rate production requirements. Clark says the facility is looking closely at options for automating every production step, from layup to nondestructive evaluation (NDE). In the meantime, she says, “I’m excited by what’s happening here. Our employees are ‘getting’ what we’re trying to do and provide a quality product. They understand that they’re going to be a part of a major ramp-up on LEAP.”

Legacy line

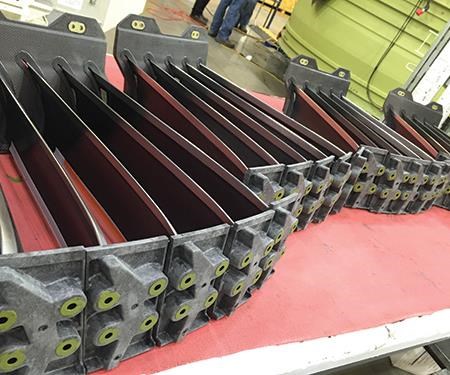

Our next stop is the cleanroom occupied by the team that manufactures GE Aviation Batesville’s highest-volume product, the fan platform for the GE90 engine. Attached to the rotating hub of the GE90, the fan platform acts as a spacer between each of the 22 fan blades. Given a build rate of 230 GE90 engines in 2015, GE Aviation Batesville is currently manufacturing fan platforms at a rate of about 5,060 per year.

Fan platform fabrication begins on one of this cleanroom’s three flatbed cutting tables, one from Gerber and two from Eastman Machine Co. (Buffalo, NY, US). These are used to cut dry carbon fiber fabrics that are subsequently kitted for preforming. Each kit is hand-laid in one of two female molds mounted in each of six Radius layup machines (12 molds in all). When layup is complete, a binder is applied, the molds are bagged and the preforms are put through a 20- to 30-minute debulk cycle. When this is complete, the debulked preforms are removed from the cleanroom and taken out to a Radius machine for RTM.

Curt Curtis, technical leader at the Batesville Composites Operation, manages the fan platform fabrication line and says each fan platform comprises five to seven preforms, depending on size and configuration. The molding process is monitored and controlled via a GE informatics system that captures and analyzes the RTM profile on the fly, helping make sure that parts are neither under- nor over-cured. The rules, says Curtis, are pretty basic: “Get the best possible vacuum and the most possible pressure, and you’ll get a good part.”

After RTM, a fan platform is sent to be trimmed and cut on one of three Mazak Corp. (Florence, KY, US) machining centers. Following this, GE Aviation Batesville employees add wear strips, linings and silicone rubber trim for erosion protection, at which point the fan platform is ready for shipment.

Really big fan cases

In terms of size, no product manufactured at the GE Aviation Batesville facility is larger than the 2.8m diameter fan case for the GEnx engine. It’s also the first carbon fiber composite fan case ever developed for a commercial jet engine application.

It represents a massive step-change in weight savings, compared to its aluminum predecessor — 159 kg per engine and a total of 363 kg per aircraft as weight savings cascade to other aircraft components. The GEnx engine is exceptional for other reasons as well. With its 2.8m diameter fan, the GEnx on 787 aircraft offers a takeoff bypass ratio of 8.8:1-9.0:1 and takeoff thrust of 69,000-76,100 lb, placing it among the most powerful and efficient aircraft engines on the market. GE is manufacturing about 300 GEnx engines per year, which means GE Aviation Batesville must turn out roughly 6 fan cases per week.

Curtis looks back on the overall effort to convert the fan case from aluminum to composites and says the challenge, historically, always boiled down to cost. In short, composites were too expensive: “It was a constant battle,” he says. However, materials and process advancements gradually nibbled away at the cost difference, and so did the weight savings. “That 350 lb [159 kg] is a game-changer,” he contends. Compared to aluminum, CFRP “offers less hanging weight and less rotational weight. Today, cost is now, probably, very competitive.”

The layup of the fan cases is substantially automated, consisting of a mandrel fed by a roll of dry braided carbon fiber, supplied by A&P Technology Inc. (Cincinnati, OH, US). The mandrel rotates in front of the fixed spool of carbon fiber, allowing the braid to lay over the mandrel’s surface. Then, over this braid is placed a series of epoxy resin tiles. These tiles are held in place with a silicone bladder that overwraps the entire exterior of the mandrel. The wrapped mandrel is cured for 24 hours. GE Aviation Batesville has four autoclaves, supplied by Taricco Corp. (Long Beach, CA, US) and ASC Process Systems (Valencia, CA, US), two of which are used to cure GEnx fan cases. The largest, a Taricco autoclave, is 6m in diameter by 12m long and can cure two fan cases, simultaneously.

After a fan case is cured, its inside diameter is lined with a series of eight honeycomb sandwich panels to provide an abradable surface against which the fans will rotate. As with many engines, the fans rotate in a space that must be held to very tight tolerances so as to minimize the space between the tip of the fan blade and the inside of the fan case, without impinging on the rotation of the blades. The abradable panels provide a surface into which a fan blade path will be cut, after case assembly, to allow that final measure of clearance.

Also installed are a series of hat stiffeners and metallic inserts for load spreading. In the next step, the composite fan case is mated with the aft fan case, the green structure atop the composite fan case in the bottom photo. The aft fan case, an aluminum/honeycomb structure supplied to GE Aviation Batesville by a third party, eventually will be bonded to the engine core.

After the two fan cases are mated, technicians work on the inside diameter of the fan case to cut the final fan blade path. Other technicians will add to the exterior of the fan cases a variety of brackets, tubes, oil tanks and other equipment. At this point, GE Aviation Batesville’s work is done and the entire structure is shipped to another GE Aviation plant, in Peebles, OH, US, for testing and final assembly.

What the future might hold

The big question GE Aviation Batesville faces going forward is how much work it will win on the forthcoming GE9X, which, when it comes to market on the 777X, will be one of the largest and most powerful commercial jet engines in the world. It features an 3.6m diameter fan with 16 carbon fiber composite fan blades. It offers a 10:1 bypass ratio, up to 102,000 lb of thrust and will be 10% more fuel efficient than the GE90-115B that powers the current Boeing 777-300ER. Clark says Batesville is in the running to provide acoustic panels, stator assemblies and OGVs for the GE9X, which was expected to undergo its first tests in March. Whatever the outcome, with a team-oriented workforce that is clearly invested in the technologies it uses and the products that result, Batesville is well-positioned to absorb a variety of composites work over the next several years. And, with workforce-development partnerships with Northwest Mississippi Community College (Senatobia, MS) and the University of Mississippi (Oxford, MS), there appears to be a strong network in place to ensure that GE Aviation Batesville will continue to attract the type of coachable and invested employees that have made the facility the success that it is.

To be sure, on the technology side, GE Aviation Batesville is not sitting still. Clark says GE Aviation is considering adding multi-cavity RTM capabilities, and there is room for another large autoclave. And entirely new technologies might also be in store. The sheer quantity and quality that will be required of commercial jet engine manufacturers during the next 30 years promises that the Batesville plant will be a busy one.

“We are trying to create an environment and a workforce and facility that is lean, flexible, adaptive, knowledgeable and invested in the work and the product,” says Clark. “We think we are in a very good position to do just that.”

Related Content

PEEK vs. PEKK vs. PAEK and continuous compression molding

Suppliers of thermoplastics and carbon fiber chime in regarding PEEK vs. PEKK, and now PAEK, as well as in-situ consolidation — the supply chain for thermoplastic tape composites continues to evolve.

Read MoreVIDEO: One-Piece, OOA Infusion for Aerospace Composites

Tier-1 aerostructures manufacturer Spirit AeroSystems developed an out-of-autoclave (OOA), one-shot resin infusion process to reduce weight, labor and fasteners for a multi-spar aircraft torque box.

Read MorePlataine unveils AI-based autoclave scheduling optimization tool

The Autoclave Scheduler is designed to increase autoclave throughput, save operational costs and energy, and contribute to sustainable composite manufacturing.

Read MorePlant tour: Airbus, Illescas, Spain

Airbus’ Illescas facility, featuring highly automated composites processes for the A350 lower wing cover and one-piece Section 19 fuselage barrels, works toward production ramp-ups and next-generation aircraft.

Read MoreRead Next

Aeroengine Composites, Part 2: CFRPs expand

Proven in fan blade/case applications, carbon fiber-reinforced polymers migrate to previously unanticipated destinations nearer the engine “hot zone.”

Read MoreDeveloping bonded composite repair for ships, offshore units

Bureau Veritas and industry partners issue guidelines and pave the way for certification via StrengthBond Offshore project.

Read MorePlant tour: Daher Shap’in TechCenter and composites production plant, Saint-Aignan-de-Grandlieu, France

Co-located R&D and production advance OOA thermosets, thermoplastics, welding, recycling and digital technologies for faster processing and certification of lighter, more sustainable composites.

Read More