Share

Read Next

The One South First building, part of Domino Park in Brooklyn, N.Y., features a concrete facade fabricated, in part, with composite molds produced using a large-format additive manufacturing machine. Source | Max Touhey

Every multi-story building constructed today requires a facade. Derived from the French word façade, which in turn came from the Italian facciata, it means “face.” In short, the facade is the exterior, public-facing structure that gives the building its character, color and shape. For architects, the facade very much sets the tone for the rest of the building and says much about the designer’s architectural intent.

A facade is also functional. It provides the structure that surrounds windows and doors, protects the building from weather and impacts, and affects the building’s energy efficiency. A facade can be constructed from a variety of materials, including composites, stone, steel, glass or concrete. Concrete in a facade, by virtue of its formability, can be used to give a building a highly dimensional and visually impactful appearance, particularly if the concrete shapes are varied.

The 45-story One South First building (far left) in Domino Park features a facade designed to emulate the crystallinity of sugar, a nod to the 138-year-old Domino Sugar refinery (with smokestack) that is the centerpiece of the site. Source | COOKFOX

Sugar is king

This was the case at Domino Park, an 11-acre redevelopment project along the Williamsburg waterfront in Brooklyn, N.Y., U.S. At the heart of Domino Park is the 138-year-old Domino Sugar Refinery, which closed in 2004 and is now being renovated as office and retail space. Part of Domino Park includes several new buildings, including the 45-story One South First and the conjoined 10 Grand. For these buildings, the architect, COOKFOX (New York, N.Y.) decided to use a concrete facade that features multiple surface angles, multiple window frame shapes and multiple window frame widths to, from a distance, loosely convey a sense of sugar crystallinity, in keeping with the site’s history.

Gate Precast Co. (Jacksonville, Fla., U.S.) won the contract to construct the concrete facade — basically, a series of window frames — for the One South First project. The company would, as is typical for a concrete facade, fabricate the frames at its own facility and then ship finished frames to the work site where they would be hoisted into place for installation via crane. If Gate had decided to follow tradition, it would have built wooden molds with which to shape all of the concrete frames. Gate, however, decided not to follow tradition.

“If [composite] molds are taken care of properly, we think they can be used hundreds and hundreds of times.”

To understand, go back to 2017, when Gate partnered with the Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute (PCI, Chicago, Ill., U.S.) and Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL, Oak Ridge, Tenn., U.S.) to conduct a preliminary assessment of the use of large-format additive manufacturing to build composite molds for in-plant precast concrete forming. This assessment was done using a BAAM (Big Area Additive Manufacturing) machine at ORNL. BAAM is a large-format additive manufacturing machine with a 25-square-meter build envelope, co-developed by ORNL and Cincinnati Inc. (Harrison, Ohio, U.S.) Gate committed to build composite molds for the One South First façade. The project required 80 molds total, 37 of which would be printed. The remaining 43 would be made from wood. By the time this decision was made, timelines for mold delivery was tight.

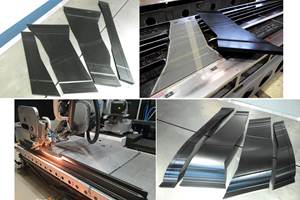

One of the AES composite molds being finished via CNC after it was built in a BAAM machine. Material, supplied by SABIC, is an ABS with 20% chopped carbon fiber reinforcement. Source | AES

In 2016, Additive Engineering Solutions (AES, Akron, OH) had acquired its first BAAM machine from Cincinnati Inc. Because of that, ORNL and Gate Precast turned to AES for help. Andrew Bader, VP and co-founder of AES, says his company and ORNL split the work package, with AES producing 18 of the 37 molds. Bader says each window frame mold measures about 5-6 feet wide, 9-10 feet tall and 16 inches deep and weighs about 500 lb.

Bader says the interior of the geometry of the molds, because they are designed to produce frames that surround rectangular windows, was relatively simple. However, the design of the exteriors surfaces of the frames, as noted, was more complex, with varied depths and angles integrated into each mold. One printed form replaced a wood form composed of many individually cut pieces nailed together. “The geometry was simple, but complicated,” Bader says. “The project required several unique frame designs, depending on frame location.”

For part of its production, AES chose an LNP THERMOCOMP AM compound, a high-modulus, low-warp material based on ABS with 20% chopped carbon fiber reinforcement supplied by SABIC (Houston, Tex., U.S.). Bader says it took the BAAM machine 8-10 hours to build each monolithic mold, followed by 4-8 hours of machining and finishing in a Quintax (Stow, Ohio, U.S.) CNC machine. He reports that the molds were sanded to the required dimensions, but not sealed.

Two of the AES-built composite molds (background) are ganged with a traditional wood mold (foreground) in a three-window frame at Gate Precast in Winchester, Ky., U.S. Source | AES

Fabricating window frames

The molds were delivered to Gate’s Winchester, Ky., U.S., facility where they were used alongside the 43 traditional wood molds that Gate built for the project. The wood molds were hand-assembled by Gate employees, then a fiberglass mat and resin coat were applied, with form oil sprayed on to facilitate release of formed concrete frame. Form oil was also sprayed on the composite molds to facilitate release.

To perform a concrete pour, multiple molds were placed on a wood casting table 40-50 feet long. Molds were ganged in to produce a single frame, a double frame or a triple frame. Steel rebar was positioned inside each mold and concrete was poured around the rebar. The casting table was then vibrated to consolidate the concrete. After 14-20 hours of cure, the window frames were demolded, acid washed and polished. Then, the windows were installed and the entire package was shipped by truck to the construction site in Brooklyn.

Bader says the AES composite molds, working alongside the traditional wood molds, quickly revealed their advantages. First, he says, a wood mold only allows 15-20 concrete pours before it must be removed from service and refurbished or replaced. The AES molds, conversely, allowed 200 concrete pours with minimal refurbishment or out-of-service time. And the 200 pours, says Bader, represented the end of the project, not the end of the mold’s service life. “That’s just where they stopped,” he says. “If our molds are taken care of properly, we think they can be used hundreds and hundreds of times.”

Finished concrete frames fabricated by Gate Precast await transport to the One South First site in Brooklyn. Source | AES

Further, for usage of 150 pours or more, Gate calculates that it would have taken up to 10 wood molds to meet the performance of one AES mold. Also, given that it takes Gate 40 man-hours to produce a wood mold, without the 37 composite molds the company would not have met the schedule requirements of the One South First project.

Bader concedes that an AES composite mold costs four times as much as a wood mold, but is at least 10 times more durable. “The way precast forms have been built has remained relatively unchanged for decades,” Bader asserts. “All of a sudden, one day, we’re making 500-lb 3D forms and everyone was shocked.” That said, he acknowledges that additive manufacturing such molds is most cost effective in applications where concrete forms have complicated geometry or high repetition — same form many times.

AES, Bader reports, now owns and operates four BAAM machines and can produce parts up to 8 feet tall. Much larger parts have been constructed by joining multiple pieces.

A concrete frame with windows installed is hoisted up for installation on the One South First building. Source | COOKFOX

Related Content

3D-printed CFRP tools for serial production of composite landing flaps

GKN Aerospace Munich and CEAD develop printed tooling with short and continuous fiber that reduces cost and increases sustainability for composites production.

Read MoreTU Munich develops cuboidal conformable tanks using carbon fiber composites for increased hydrogen storage

Flat tank enabling standard platform for BEV and FCEV uses thermoplastic and thermoset composites, overwrapped skeleton design in pursuit of 25% more H2 storage.

Read MoreEaton developing carbon-reinforced PEKK to replace aluminum in aircraft air ducts

3D printable material will meet ESD, flammability and other requirements to allow for flexible manufacturing of ducts, without tooling needed today.

Read MoreOptimizing a thermoplastic composite helicopter door hinge

9T Labs used Additive Fusion Technology to iterate CFRTP designs, fully exploit continuous fiber printing and outperform stainless steel and black metal designs in failure load and weight.

Read MoreRead Next

Developing bonded composite repair for ships, offshore units

Bureau Veritas and industry partners issue guidelines and pave the way for certification via StrengthBond Offshore project.

Read MorePlant tour: Daher Shap’in TechCenter and composites production plant, Saint-Aignan-de-Grandlieu, France

Co-located R&D and production advance OOA thermosets, thermoplastics, welding, recycling and digital technologies for faster processing and certification of lighter, more sustainable composites.

Read MoreAll-recycled, needle-punched nonwoven CFRP slashes carbon footprint of Formula 2 seat

Dallara and Tenowo collaborate to produce a race-ready Formula 2 seat using recycled carbon fiber, reducing CO2 emissions by 97.5% compared to virgin materials.

Read More