Legacy applications: Inspiration for future vehicles?

Dale Brosius, a consultant and president of Quickstep Composites (Dayton, Ohio), looks back at past automotive composites applications for today's market opportunities.

I attended the Society of Plastics Engineers Automotive Innovation Awards dinner on Nov. 6, 2013 (full disclosure: I am one of the event’s blue-ribbon judges), where a number of excellent applications of plastics from around the globe took awards. Award categories included Powertrain, Body Exterior, Body Interior and others, and at the end of the evening, one of the category winners is selected for the Grand Award. The big winner in 2013 was an all-olefinic liftgate for the Nissan Rogue, consisting of a thermoplastic olefin (TPO) outer skin and a long glass fiber-reinforced polypropylene structural inner panel. The assembly is 30 percent lighter than the stamped-steel version it replaces — a considerable weight savings. It will be interesting to see if Nissan adopts this technology on the Murano and the Juke, two other crossover SUVs in its line — and if other OEMs will introduce similar technology.

The automotive industry is rife with good applications that failed to proliferate to other models built by the same OEM, let alone to other OEMs. This lack of proliferation has been a great source of frustration for Tier 1 suppliers and those who supply composite materials to them. Almost every composite materials supplier has looked at the automotive industry and, noting that the average vehicle weighs roughly 1,500 kg/3,300 lb, asked, “How hard could it be to get just 1 kg on every vehicle?” The answer — no surprise to industry veterans — is “very hard.”

New materials earn their way onto vehicle platforms, one application and one model at a time. Although it seems logical that when a part offers weight or cost savings to one OEM, other OEMs would line up to gain the same advantage, it rarely works that way. OEMs differ in engineering philosophies and risk-taking perspectives; and then there’s the “not invented here” syndrome. Given the new pressures to increase fuel economy and reduce CO2 emissions, and the advances in composites manufacturing technologies, maybe it’s time to revisit some composite solutions from the past and see if they can be reprised in vehicles now on the drawing board.

For inspiration, I looked back through the list of previous SPE Grand Award winners. Some applications, like polyamide radiator end caps (1981 winner), thermoplastic air-intake manifolds (1994) and integrated front-end systems (1995) have, indeed, managed to catch on across multiple platforms and OEMs. However, several structural composite winners saw brief periods of expansion, followed by contraction, but are by no means obsolete.

In 1980, for example, General Motors won the Grand Award for the transverse fiberglass/epoxy filament-wound leaf spring used on the Corvette front and rear suspensions. In addition to saving weight, the spring enabled the designers to lower the hood line, improving aerodynamics and styling. In the late 1980s, GM extended the concept to a line of minivans and to large-volume, midsize passenger cars, before moving back to coil and strut suspensions in subsequent models. The Corvette still uses composite springs, but no other vehicle does. Ford developed composite springs for the Ranger pickup that proved much more durable and 75 percent lighter than multileaf steel springs, but they never made it into full production. Given today’s faster curing resins and improved winding machines, it seems a good time to take another look at composite suspensions. (For more on composite leaf springs, see the article titled "Composite leaf springs: Saving weight in production suspension systems," under "Editor's Picks," at top right.)

In 1984, I attended my first SPE Automotive Awards ceremony, where the filament wound carbon fiber/vinyl ester driveshaft used on the Ford Econoline van took the Grand Award. My employer at the time, Dow Chemical Co. (Midland, Mich.), supplied the vinyl ester resin for this application, which saved considerable weight and was less expensive (despite the high cost of carbon fiber in 1984) than the two-piece steel driveshaft design. General Motors followed a few years later with a version where carbon fiber/vinyl ester was pultruded over a thin aluminum sleeve, and installed on numerous pickup trucks over a period of about five years. Today, no North American vehicles have carbon fiber driveshafts, although a few models in Japan employ the technology. With today’s carbon fiber prices and fast-curing epoxy resins, the economics, again, could be attractive.

In 2005, the Honda Ridgeline won the Grand Award for its sheet molding compound (SMC) pickup box with an innovative in-bed “trunk” storage system. In 2001, Ford had pioneered an SMC box in its Explorer Sport Trac, which remained in production until 2010. In 2002, General Motors introduced a one-piece composite box as a factory alternative to the standard steel box. Molded using directed-fiber preforms and the SRIM (structural resin injection molding) process, the 6.5-ft/2.0m long box shaved 50 lb/22.7 kg in weight vs. the steel box, and went on the vehicle in the same assembly line. Although it was a technical success, dealers were given little incentive to promote the composite box, so the option was discontinued after a couple of years. In 2006, a new Toyota Tacoma pickup model was introduced with an SMC box. Today, only the Ridgeline and the Tacoma have composite boxes. Compared to other options for saving weight in trucks, this definitely seems like an idea worth revisiting.

While it’s easy to become infatuated with the “next big thing,” like the carbon composite passenger cell in the BMW i3, there’s good reason to take a look at what worked in the past and take advantage of new design software and manufacturing technologies that can breathe fresh life into those applications for future vehicles. Sometimes, a little nostalgia isn’t such a bad thing.

Related Content

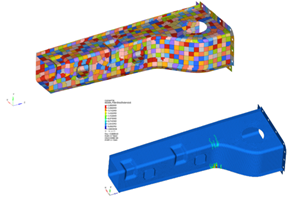

SMC simulation tool enhances design optimization

CAMX 2023: FiRMA, Engenuity’s new approach to SMC, uses a predictive technique that accurately reflects material properties and determine the performance range an SMC part or structure will exhibit.

Read MoreJohns Manville launches multi-end roving MultiStar 272

Multi-end fiberglass roving serves as a reliable product for SMC compounders aiming to excel in automotive applications.

Read MoreMatrix Composite highlights carbon fiber SMC prepreg Quantum-ESC

Prepreg produced by LyondellBasell features high flow, rapid tool loading capabilities.

Read MoreComposite materials, design enable challenging Corvette exterior components

General Motors and partners Premix-Hadlock and Albar cite creative engineering and a move toward pigmented sheet molding compound (SMC) to produce cosmetic components that met strict thermal requirements.

Read MoreRead Next

Plant tour: Daher Shap’in TechCenter and composites production plant, Saint-Aignan-de-Grandlieu, France

Co-located R&D and production advance OOA thermosets, thermoplastics, welding, recycling and digital technologies for faster processing and certification of lighter, more sustainable composites.

Read MoreDeveloping bonded composite repair for ships, offshore units

Bureau Veritas and industry partners issue guidelines and pave the way for certification via StrengthBond Offshore project.

Read More