To boldly go . . .

In 50 years, how we will look back on this new age of corporation-led space flight?

Four years ago, in the fall of 2014, Virgin Galactic was, by all accounts, well on its way to becoming the first space tourism service provider. The company, through its subsidiary The Spaceship Co. (TSC), built its carbon fiber-intensive, eight-passenger SpaceShipOne craft and had been busy testing it throughout the year. It had constructed a new and impressive launch facility near Las Cruces, NM, US, called Spaceport America.

Spaceport America would be the starting and end point for passengers who would pay $250,000 each to ride in SpaceShipOne to the edge of the Earth’s atmosphere — an altitude of about 351,000 ft/110,000m — at which point they would be allowed to unbuckle from their seats and enjoy about 7 minutes of weightlessness, plus an unbeatable view of Earth, before gliding back to the ground. As of July 2018, some 600 people had signed up for a chance to have this experience.

Then, in late October 2014, during a test flight of SpaceShipOne, as the spacecraft was still in powered flight and approaching its apogee, co-pilot Michael Alsbury prematurely and inexplicably activated SpaceShipOne’s feather mechanism. The mechanism rotates the wings to a vertical orientation and help guide the craft, shuttlecock-like, for its return to Earth. However, its premature activation destroyed SpaceShipOne, causing it to break apart. Alsbury was killed; pilot Peter Siebold, although injured, miraculously survived.

There was plenty of blame to go around for this accident. The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) in 2015 issued its report on the accident and pointed to inadequate safety standards, lack of regulatory oversight and co-pilot error. Further, the NTSB noted, SpaceShipOne should have had mechanisms in place that would have made premature feather activation impossible.

In the meantime, Virgin Galactic and TSC went back to the drawing board and started working on SpaceShipTwo (also called VSS Unity), and you can read about that spaceship and the composites fabrication being done for it, starting on p. 32 of this issue of CW. VSS Unity is now going through flight testing of its own and, in late May 2018, completed its second supersonic flight, reaching an altitude of 114,500 ft/35,000m. With the 2014 accident surely weighing heavily on Virgin Galactic, it is taking its time testing VSS Unity. As a result, it has not yet committed to a service start date.

Virgin Galactic, of course, is not the only company pursuing space tourism services. Blue Origin is working on its own craft, New Shepard, which will take passengers to 351,000 ft/110,000m for a similar suborbital experience. Other companies are working on plans for space hotels, lunar tours and more.

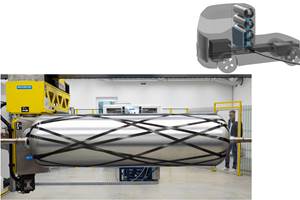

We look to these programs with some excitement because all of them do or will make substantial use of composites, in everything from passenger and crew structures to launch vehicle bodies. Indeed, when fighting gravity, as all spacecraft must, reducing vehicle mass is a necessity, and that is where composites typically excel.

Accidents like SpaceShipOne’s, however, give us pause, and remind us that sending humans into space is difficult and fraught with danger. The challenges faced today by Virgin Galactic and others put in stark relief the challenges associated with man’s attempt, nearly 50 years ago, to land on the moon. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s first steps on the moon in July 1969 are, today, taken for granted as established, successful historical events. However, the Apollo 11 moon mission (heck, the entire Apollo program) seems nearly miraculous when you consider the meager materials, computing and communications technology available to us at the time.

And so I wonder, in 50 years, how we will look back on this new age of corporation-led space flight. Will we see here the seeds of programs destined to populate the moon and Mars? Will we, eventually, take for granted the complexity and risk associated with breaking away from Earth’s gravity? What challenges will we face 50 years from now that, today, are purely speculative?

Stay tuned.

Related Content

The potential for thermoplastic composite nacelles

Collins Aerospace draws on global team, decades of experience to demonstrate large, curved AFP and welded structures for the next generation of aircraft.

Read MoreCryo-compressed hydrogen, the best solution for storage and refueling stations?

Cryomotive’s CRYOGAS solution claims the highest storage density, lowest refueling cost and widest operating range without H2 losses while using one-fifth the carbon fiber required in compressed gas tanks.

Read MoreThe state of recycled carbon fiber

As the need for carbon fiber rises, can recycling fill the gap?

Read MoreSulapac introduces Sulapac Flow 1.7 to replace PLA, ABS and PP in FDM, FGF

Available as filament and granules for extrusion, new wood composite matches properties yet is compostable, eliminates microplastics and reduces carbon footprint.

Read MoreRead Next

“Structured air” TPS safeguards composite structures

Powered by an 85% air/15% pure polyimide aerogel, Blueshift’s novel material system protects structures during transient thermal events from -200°C to beyond 2400°C for rockets, battery boxes and more.

Read MoreVIDEO: High-rate composites production for aerospace

Westlake Epoxy’s process on display at CAMX 2024 reduces cycle time from hours to just 15 minutes.

Read MoreCFRP planing head: 50% less mass, 1.5 times faster rotation

Novel, modular design minimizes weight for high-precision cutting tools with faster production speeds.

Read More